The most notable thing about Richard Chartier‘s latest is that it starts with so many organic sounds. The naturalism is startling, given his repertoire often focusing on severe, digital minimalism. For Interior Field, Chartier used field recordings from a variety of spaces, both large and small around the world. The triangulation of location, focus, and experience informs the often haunting aesthetic of the album, about an hour of sound split into two halves. Fair warning that to best experience the album, I highly recommend a good set of headphones in a quiet space. I was not able to really appreciate the complexity and range of its sounds with my windows open (although one might argue that the environment outside merely adds another layer to the listening experience) or on my open monitors, where a conspicuous fan in my amp dominated over the subtleties of Chartier’s arrangements.

Part one starts with unusual concrete sounds that at first resemble water drops on a surface… or is that the creaking of wood? The ambiguity of the source of the sound is at first curious and then fascinating. Even the sedate drones that underpin the front end of the piece feel more organic in nature, as if they are environmental or contact sounds that have been manipulated and pitched down. Fans of Chartier’s knack for sculpting minimal microtonal drones will not be disappointed, though — he delivers that in spades here, building on the more acoustic sounds that start things off and then forming a subtly undulating fabric of sonic threads.

Sine waves, hums, hiss, and tiny drones all shift shape as gradually as they originally come into focus. They share the same drowsy, slow morph of his Recurrence album released last year, but the end effect and atmosphere are distinctly different. Chartier’s sleight of hand is more refined than ever here, with gradual changes in sound that seem so effortless they are almost unnoticeable at first. By the time I realise the sound has evolved, it’s in a totally different place and shape from where it started; that sort of slow motion is not easy to achieve.

The earthiness of Chartier’s arrangements here reminds me at times of the grimy, post-industrial landscapes of David Lynch and Alan Splet‘s Eraserhead soundtrack. The second segment of the first half has a more overt rhythm to the sound, like moving parts patiently working in tandem, before settling back into a more comfortable, continuous low hum. I can’t fully do the music justice in writing about it here — there is something special about Chartier’s ear and abilities to finely design sound that really resonates here.

The second half of the album picks up where the first left off, although it feels like somewhat of a corollary to the broader arc of the first part. I say this because while it shares the same combination of natural texture and drones and atmosphere, it is far more subtle and more even than the front half. Continuous, steady rain provides the texture throughout most of the track, along with quiet, low drones that come and go even more subtly than in the first.

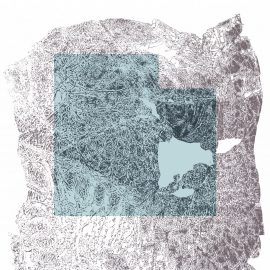

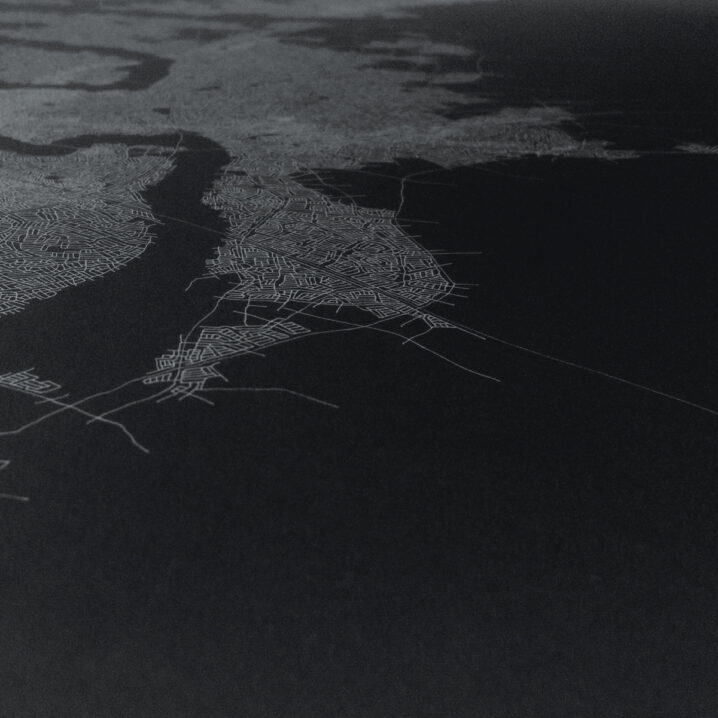

In an offline conversation with HC, Chartier revealed that the source of sounds in Part 2 of the Interior Field were recorded in near complete darkness in one of the chambers of the McMillan underground sand filtration tanks, used to store overflow storm water to prevent flooding. The sounds were captured as it the rain dripped down upon the large grids of sand, before traversing the four feet of depth into the reservoir. See photo above which should enhance this listening experience.

The distinction between the two pieces is I suppose like comparing two swatches in a greyscale: relatively different, but only on a micro level. However, they combine to form yet another stunning entry in Chartier and Line’s respective discographies. It’s nice to hear him working with field recordings in a way that feels so entirely different than a sound recordist like Chris Watson. Watson aims to preserve and emphasise the source material in as meticulous and pronounced ways as possible, whereas Chartier uses his recordings to help create a broader sound that seems more concerned with space and tone in nuanced and various ways rather than a focused fascination on the source itself. Highly recommended.

Review by Matthew Mercer of Ear Influxion.

Additional comments on source of the material in Part 2 by HC.