Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

I began composing music around age 11. My first pieces of gear were a Wurlitzer Centura Organ and a Heath-Kit stereo cassette recorder. The organ also had its own cassette recorder installed in the bottom manual. So, right away, I began experimenting with composing and overdubbing between the two cassette recorders. A very primitive way to start, of course. I spent hours and hours each day working with it. I eventually added a Realistic/Radio Shack reel-to-reel and a stereo mixer, given to me by a really kind, encouraging school bus driver. I loved that setup so much and still have tapes from those days somewhere here. It really got me moving quickly in the right direction, learning music and composing my own.

I would check out records and cassettes at my local library and learn Bach, Buxtehude, and Pierre du Mage pieces by ear and would simultaneously read sheet music with the pieces. After hearing composers like Ligeti, Webern, & Ussachevsky, I wanted to try to explore those atmospheres and sounds on my organ and tape recorders. Just learning how to combine, mix, and blend things, using the vari-speed and reverse of the tape decks. Panning tracks on the mixer and, of course, drenching everything in spring reverb. It was the start of a long journey of a deep passion for the sound of the music. After about 3 years with that setup, my mother remarried, and I had to leave all of my equipment behind. It was pretty devastating, really. However, it never discouraged me. I kept on working in any way that I could. I began to learn other instruments like drums, guitar, flute, and French horn. Just to keep learning everything I could and find opportunities to make music. The library was my home and haven. Then, my sacred space…

By the time I was 16, I was teaching at a local music store in the evenings and weekends. Playing in rock/country bands, churches, weddings, riverboats, and hotels, and playing gigs with some of my teachers. It was an exciting time. All of which got me a job at a local jingle music studio. Doing session work and various odd jobs like learning how to edit magnetic tape and program sequencers and some studio techniques. It was there I discovered instruments like the Fender Rhodes piano, an ARP Odyssey and a Minimoog that they had stored in the storage room repair shop in the back of the studio. One night after a session, when I was alone at the studio, I really wanted to try those instruments. I dug them out, cleaned them up and when I played them for the first time, it was a life-changing experience. The touch response and immediacy of the dials just made me feel so connected to what I was playing or creating. I was in there exploring well into the next morning…

When the studio owners returned, they weren’t too thrilled that I dragged all this “old junk” back into their studio. However, they were endreared and supportive of my excitement. So they cleared out an adjacent small storage room and allowed me to set up my own little workspace. It had an ivy-covered window, a rugged workbench, an old couch and a coffee maker. They kindly provided me with an 8-channel Tascam reel-to-reel, a set of old JBL studio monitors and a Teac two-track reel. As long as I kept that stuff out of their “state of the art” recording studio, I could work in that room after hours. I basically lived there. I rarely ate or slept. Didn’t need to. I was overjoyed to have such an opportunity. Soon, I bought my own Fender Rhodes and an ARP Omni. A Moog Prodigy, Jen SX 1000 and a Roland RE-301. Then, my own ARP Odyssey. Which opened up so many doors to my creation. I spent more money each week on magnetic tape than food. The studio owners would often give me old magazines, books, and records to learn more about music, recording and equipment. I began reading a plethora of “Modern Music and Recording” and “Mix” Magazines from the 1970s. I was taking classes at the local university and discovered the music of George Crumb, Ben Johnston, and John Adams. I was so inspired by the directions those composers were taking and wanted to find my own way into those destinations.

The studio owners also gave me a copy of Weather Report’s “Heavy Weather” LP and told me to listen to it in headphones. I did, and it blew my mind. Of course, the musical performance was awe-inspiring, but it was also the sound design of it all. The stereo soundstage on that record is so incredible and seems to keep opening up into a wider view as you listen. This time was indeed an epiphany for me. I wanted that range that the modern classical composers were wielding. Yet, I wanted to use the color and orchestral control of my analog synthesizers. On the Weather Report album, I kept seeing this “ARP 2600” Synthesizer listed on every track. I dug deeper into my stack of books and magazines and finally read about it and saw some photographs of this magical instrument. It certainly appeared more complex and expansive than my Odyssey. Soon, I was off on the hunt for one. There was a guy named Dave Thompson AKA “Synthlocater”, in the back of Keyboard Magazine. I called him about it, and he said he had a couple of ARP 2600s. So I drove almost 5 hours to visit him and try one. Soon, I saved and saved and returned to buy one. Then another 2600. Interfacing the two ARP 2600 and Odyssey together with incredible results. Soon, I added Oberheim DS-2 and ARP 1601 Sequencers.

I was off and running. Working 7 days a week. Teaching, playing various gigs, and sessions at 2 jingle studios. I also worked in warehouses and factories to keep money coming in. Eventually, I moved into my own place. A four-room house where I wrote and recorded my first cassette release, “Snowy Dreamscapes”, in the winter of 1993. Reissued in 2019 by Imperial Emporium Records in Akron, Ohio.

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

O dear, that would be difficult for me to clarify… Since my little shack studio in 1993. I’ve probably moved the studio 10 or 12 times. It’s been quite a commitment to keep it all together. I’ve gone through many times of desolation and sacrifice, no doubt about it. However, I always have found a way to build it back again. 6 years ago, I made the decision to move out of the city and back into the countryside. It’s full circle. There is a clarity and connection that I have with this area that I can’t seem to get anywhere else. I feel closer to the source of the music and the sound of everything. Also, I have a daughter whom I love to witness growing up out here. I wanted her to have some of the same positive impressions that I had growing up in a rural environment. To be creative, explore, and develop a mind and spirit of her own. Now, children have the computer as well. So they have the best of both worlds.

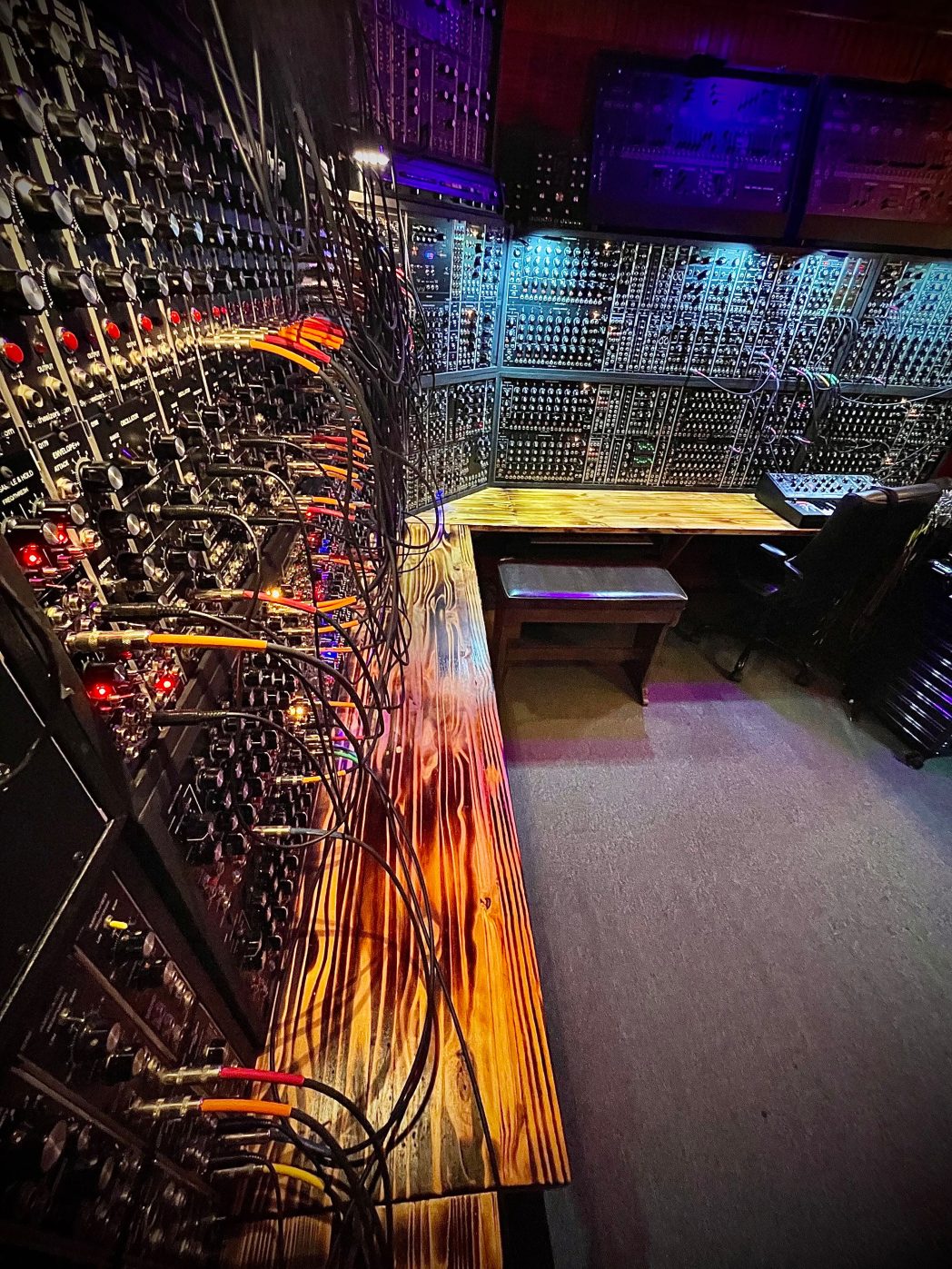

My studio is now small and cozy, but I have completely streamlined and expanded the possibilities since moving out here. It’s a 20X15 cedar room with a few beautiful windows overlooking the countryside. I have custom-made, sturdy workbenches installed all around the perimeter. Facing the windows is my recording and mixing center with all rackmount interfaces, mixers, processors, and patch bays, my computer, tape machines and Focal studio monitors. Other than that area, All the other walls are large format (5U) modular synthesizer cabinets. It’s a mammoth, totally custom-made system. Essentially, it is a most expansive and heavily modified Moog Modular system. One wall of cabinets is filled with small format modular synthesizers (Eurorack). There’s a pair of ARP 2600s installed, and another pair of parallel Focal studio monitors.

All of the modular system trunk lines are wired with custom Mogami cables around the studio and into the patch bay. The studio is interfaced with a Garfield Time Commander, which serves as a master clock/logic for the entire studio. Whether I am recording to tape or multiple tape machines, the computer, a 24-channel digital tape recorder or a combination. There is little to no resistance in interfacing all of the tools needed to complete a piece of music quickly and efficiently. It’s the most firepower I’ve ever experienced in any studio anywhere in the world. It’s so efficient and so easy to compose and record with. As well as working on multiple projects simultaneously.

The workbenches are large enough that I can bring a plethora of other keyboards or synthesizers into the studio and immediately interface them. It’s truly a lifelong dream finally realized. It was also a great way to sell off lots of other synthesizers and gear that weren’t really getting fully utilized and weren’t worth the cost of keeping them serviced and refurbished. I’m a musician and composer, first and foremost. The gear and equipment are there to provide a means to realize the finished work.

Tell us about your favourite piece of hardware.

My custom modular system. It just offers an unlimited amount of musical and sonic possibilities. It’s something like 72 voices, 2 dozen filter sets, a myriad of envelopes, sequencers and modifiers etc… Also, it connects with anything and everything in the studio. I’ll always love and use my ARP 2600s. The Moog One amd all the Moog synths in my studio. My ARP String Ensembles will never leave my setup. Tascam, Otrai, and Fostex tape machines. SSL & Holland Synthesizer Mixers. They’re all part of the big picture of how I compose and record my music.

I put a lot of great care and detail into the welfare of my recordings. At the same time, I am not an artist who has the luxury of spending months or even years composing, recording, and mixing their albums. In fact, I typically make my records in less than a week. My best work is done when I am prepared and ready to go in and see a project through to the finish line. It’s part careful planning, programming, performance, and the glue is improvisation. I want to do as little composite recording and mixing as possible. I want the work to breathe. I want to retain oxygen in my mixes and create a home for my listeners in the wilderness of my music and soundstage. That is always better done in performance. It’s like playing live – you blow into a horn or develop a pattern on a ride cymbal to react to the pressure of the room and for its sensitivity within the music. It’s taken me many years to develop the techniques to obtain musical and sonic command of almost any situation I find myself in within the muse. Music and recording should always be a joy. Never a resistance to the miraculousness of the music to be made. My stride is staying out of the way of the art. Listen first and respond accordingly…

And what about the software that you use for production?

In the digital realm, I record or transfer analog tracks with a UA Apollo 16 channel I/O. Routed I/O with the Holland Synthesizer FM7202A Mixer. Recording into Logic at 24/96, or a 24-channel tape recorder. I will often mix to Otari tape or a standalone HD Digital 2-Track through 16 channels of SSL preamps/EQs. I do lots of sound design work with Waves Audio and implement a great deal of their excellent plugins when needed. Also, Universal Audio and Brainworx plugins for the master bus sound incredible. For finishing touches, I love using Cherry Audio and Moog software for a variety of analog-style signal processing. For orchestral and psychoacoustic work, I use Slate & Ash’s brilliantly flexible and incredible-sounding software.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on, and do you think one day you’ll have it?

Last year, I wrote and recorded an album at Ben Vehorn’s private studio in the Pacific Northwest, implementing large, vintage Polyfusion and custom Oberheim modular systems. Everything was recorded and mixed on a completely refurbished Otari Radar system. At first, I was sceptical that it would sound as good as today’s digital technology. Upon the first playback, I was amazed at the transient response, detail, and weight of the recordings. It sounded amazing! I loved the user interface and the resemblance to working with analog tape. Only faster and more efficient. Being able to “scrub” tracks, make immediate changes and edits on the fly, no screen is needed. You simply just walk into the studio, hit record, and you’re tracking. Just using that system had a tremendous impact on the welfare and spirit of those recordings. At some point, I want one of those systems. I do not exactly know how or why it sounds so much better than what’s available digitally now. However, my ears can hear the difference. The headroom and air was remarkable.

On the other hand, I hate the idea of dealing with such an out-of-date digital format. Same with the Synclavier. Both are sonically superior technologies, which I would love to have, but I don’t really want to have to become a full-time tech to keep them running. Also, I love the concept of not having a screen in my studio. All I want to see while composing and recording is the beautiful views outside my windows, my modular equipment, and sheet music for the session. Yet to have the recall, storage, and flexibility of digital formats would be wonderful. So, eventually… maybe when I move to the next place to build my final studio/workspace, I’ll build my main studio with a fully refurbished pair of Radar systems and analog tape machines. Then, build a smaller computer production studio with just what is needed for sound design work and music business management. Probably sounds strange, but I really want one of those systems.

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

I strive to create stereo compositions and mixes that project a tapestry of color, texture, and “air”. Not just reverbs and lots of translucence but creating a space for every element in the mix. Including musical devices like time signatures, lyrical phrasing and attention to detail in the arrangement of the piece that is unfolding. Whether a piece should feel “performed”, celestially transfigured, or a cross-current of both. It’s always intent over content for me. It’s all about creating a home for the listener in the music and sound design. An explorative wilderness of music and sound. Yet develop each destination with the focus and arrangement of a cinematographer. Envelopes are extremely important in my work. Not only to control and position a musical sound into an ensemble of others but also when I am creating sonic passageways for the listener to discover as the musical intention surrounds them.

Everything is multi-timbral. Even a single voice solo synthesizer or kick drum. To create the realism of a human experience, you have to accept the responsibility of giving your listeners more than just what comes out of the box. Everyone’s an expert on that now. Besides, the magic of synthesis is in the process. Not the recall. For example, even with harmonic and melodic intentions, say a melody line or solo. Instead of just dialling up a solo voice and taking flight, I may set up a Keyboard to CV control an alternate scale so that every time I press a note on the keyboard, there will be a slightly different temperament to each note played. Taking that particular concept further, I will set up another row of sequential controllers to create stereo symmetries between the envelopes, amps, and filters. To give the impression of not only “blowing” into a solo voice but perhaps where I am blowing, each note will move around subtly in the stereo space.

Even further… I’ll set up a row of sequential controllers that control the side chain of a stereo compressor that’s post, a lush reverb and EQ. Perhaps the reverb is very subtle until it reaches a gate in the sequence that opens up the filter/amp of a synth to a growl, and then it smacks the reverb. The EQ side chain keeps the louder synth notes from being too harsh or bright. It may also be set that it pulls and pans the signal in a certain way, which will then trigger the pre-delay of the reverb more dramatically than just the synthesizer voice residing in a static position. All of this will spill out and smear the stereo image in a way that feels more like a physical experience. Not necessarily an electronic one. As electronic composers and musicians, we have an incredible opportunity to design the space we wish for our music to live, breathe, and grow in, regardless of whatever style or level of musicality. Everyone knows the sound of something. Even if they can’t recognize one’s beautiful chord voicings or esoteric scales. Listeners can feel the sound of them and what space the sounds are resonating in.

There’s a plethora of other musical and studio techniques that I have developed and refined over the years. Phase modulation, time and temperament, pressure and contrast. Touch, tone, and taste. They are all part of the arrangement process. As for mixing, if the arrangement and performance are doing what they’re supposed to, then the recorded works will mix themselves. I’d rather spend days refining sounds and know the range and limits I have and roll tape only once. Then, start recording a piece and layer and labor over it until it becomes what it is. A sort of freeze-dried version of my original vision or intention. However, the wonderful reality about synthesis and electronic music in general is that there are still NO RULES. It’s open season. Whatever you want to do, you can. The most important part is to turn everything on and start carving out sounds and songs that suit you.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

For “Electronic Voyages”, each piece on the album had a different approach, both musically and technically. On the opening track, “Double-Image”, I wanted to just establish some deep space around a dark and spiralling riff. In the early morning, when I recorded that, there was a blizzard circling around outside the studio. I wanted the listener to feel as if they were witnessing it with me. So, I had two Moog 960 sequencers patched up into my custom ARP 2500 Multimode filter by LWSS. One 960 percolating the main sequence, while the other was transposing the chord changes of the theme. Momentarily reaching over and opening up a 9-voice Moog IIIP modular bass drone to keep the space dark but warm and roomy. Celestial, photographic ARP Strings cascading harmonic snowflakes in stereo. A Pair of ARP 2600s which were aided by external processors such as parametric equalizers and delays, created the deep psycho-acoustic in the far distance. Finally, playing the Moog One through the SSL console. Creating solemn, searching melodies. Beautiful yet dirty and edgy. Pretty much everything recorded live to 8-channel tape with the ARP 2600s overdubbed. Very raw and rock and roll. lol

“Inner Space” was composed using the first beta of Moog One’s extensive 3-channel Sequencer CV clock outputs patched into the modular wall of momentary sequencers. Creating a laboratory orchestra of counterpoint. Simple, sibilant sounds yet complex contrapuntal time signatures ornamenting the meditative, sunlit space. Again, pretty much everything here is programmed and mixed on the modular. Including the spring and plate reverb. Only overdubbing the ARP String Ensemble and Moog IIIP winds. Another mostly live to 8-Channel tape.

“Metempsychosis” is probably my personal favorite piece on the album. It is completely self-generative music. While each passage is fully composed and not random, there was a matrix of sequential switches and a myriad of envelopes used to achieve this. It took 3 or 4 days to program and get everything mixed and dialed in. If memory serves me, I believe it’s 4 or 6 trunk lines (outputs) going to tape. Carefully printed to retain the monolith low end. This piece was performed, mixed, and cut live to tape with The ARP Strings and Moog One solo voice simultaneously. I performed it once late at night and did another performance of it early the following morning. Listened to it for a few days before pulling all the cables out to start a new piece.

“Cosmotopia” was a soliloquy. This was after a busy day of other duties and sessions. Only to find out that the great Klaus Schulze had passed away. I knew that he’d been battling illness, but I heard through resources he was in good spirits and had just finished an album. So it seemed and felt unsuspected. While I was a latecomer to his music, I fell in love with it and him after discovering his amazing body of work. I also loved his honest, open, and sometimes blunt interviews. He wasn’t out to impress an audience or to follow stylistic trends. He did exactly as he damned well pleased and did it beautifully and bravely. I cherished that about him. Of course, his choice of instruments was always right in line with mine. He used what worked for him. Those kinds of actions spoke to me just as much as the music. The commitment and dedication to following the muse and not conforming. His passing hit me harder than I anticipated. It felt as if we had lost our bold, big brother. Giving us the green light to do exactly as we wished.

After some heartfelt correspondence with colleagues Harald Groskopf and Rory Kaplan, I suddenly felt clear and focused. I turned on the studio and sat down at a pair of ARP String Ensembles, both patched into ARP 2500 and Oberheim SEM filters, I had a series of keyboard-triggered, sequential controlled LFOs slowly taking turns modulating the stereo phase. A Pair of ARP 2600s blinking and communicating into the cosmic distances of space and time. Some Moog 15 winds and spaces, then I played a simple, single solo voice on the Moog IIIP. I played through it once. Singing it out loud as I played the solo. Tears slowly travelling down my cheeks. My way of saying farewell to one of the best there ever was. No true resolve, forever lost in sonic space, to be continued. Passing beyond the ivory towers of time and onto the quadraphonic doors of Cosmotopia…

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

Lots of variables here. For shows I travel by ground, I’ll take a four-cabinet modular system, a 16-channel mixer. A Moog solo synthesizer or ARP Odyssey and either a digital mellotron, organ, or polyphonic. Depending on the venue, promoter, and the intention of the event, I will compose, program, and mix for that from scratch on-site. I usually wear headphones, and then I’m ready for soundcheck. My dear friend and technical assistant, Brandon Reisig travels with me to most gigs and is such an immeasurable reinforcement. We have it down to a science, and it’s always so much more fun. He, too, is an incredible modular synthesist, so the language we speak is of the same nomenclature. Sometimes, when set time allows, he will perform with me on a few numbers, which is always a great way to conclude live concerts. When I am traveling by air or sea, then I work with hosts or promoters to secure a solid backline for the concert. I have been extremely fortunate with some truly incredible and kindly accommodating hosts. It always fills me with such gratitude and it only fuels the fire to give them and the audience their money’s worth. Of course, years ago, it was very rough and tumble. You never knew what you were going to have for the night. or whether what you had was going to work. I will typically take all my own cables and FX. Or I will travel with my ARP 2600 Mini, Moog Mother 32 and Werkstatt packed in the flight case. I can certainly get through the gig with that rig if everything else fails.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace, and what would be a particular element that you would improve on?

Everything. I love nature and the ability to just slide the studio door open and hear the sounds and smell the fresh air, especially in the early morning or evening. The air is just crystalline. We have hiking trails cleared all around the woods where we live. So I can take breaks and just go outside and get away from the computer and the phone on days that allow it. I have PA speakers I can easily place right outside, which allows me to listen to patches or pieces I’m developing outside. That usually will inspire some other level or layer of detail when I go back into the studio. I love that my studio is all cedar wood and glass, with a tin roof. No concrete or plaster. My studio is adjacent to our kitchen here, which allows me to still do all the things I do for my family while working. My daughter can be working on homework, and we can have eye and ear contact without leaving our workstations. We homeschooled here for a year, and that was actually really wonderful. Even though it was different and challenging. The setup here really made that year a great success. I love that the ceilings here are arched from front to back. It sounds good here, and even though this is a small space, it never feels cramped. The highest part of the ceiling is around 15 ft. Also, The equipment setup here is always awe-inspiring. I never walk into this room and do not feel inspired in some way. Even on really long, difficult business days, which there are plenty of, lol!

If I were to improve on this workspace, it would be to have a little more room or another room attached. I can’t set up a bunch of keyboards here permanently and don’t wish to. But it would be nice to have another room where all the keyboards and percussion could be set up and ready to patch in. Maybe a space big enough to have a nice couch and atmosphere. It’s pretty comfortable here, though. There’s a total of 4 comfortable office chairs and a few bean bags for when friends, colleagues, and students come to visit. I love all of the sounds outside that progress through the day and the seasons. There is always something to tune your attention to and listen to. Even the crystal silence of the winter nights.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

It usually starts with either some time outside in the early morning or evening. Going out and getting lost in nature really allows me to find my muse. Once you’re really tuned into it, it becomes such a timeless space. Everything in the muse begins to operate on its own celestial algorithm. The subconscious self has room to explore and roam. Tuning into the sounds of the wildlife of nature provides an ever-evolving clarification of what my synthesis becomes.

Many years ago, I developed a personal method and nomenclature of interpolating both Western musical notation and audiology graphs. I would use the graphs to document the frequencies of everything I would hear around me. Pitch, modulation, amplitude, distance, depth, timbre… also, where it would travel within a quadraphonic space. I would spend hours and hours recording this information manually and then take it back to the studio for further interpretation and investigation. I would dial up these discoveries on my modular synthesizers and follow down each segment one by one. Either editing them together in chronology, or mixing them together to create a more subtle and complex psycho-acoustic experience. I would also arrive at many unique musical passages and devices simply by taking the same set of frequency calculations by rounding them to the nearest quantized value. It’s an amazing way to work and liberate yourself from taking the same approach for every project. Also, sometimes I just sit down, turn on an instrument and just play. Allow the inspiration to evoke and arrive by all means necessary. I sing lots around the house, and I feel that’s important for any instrumentalist. It’s your body resonating and expressing our own touchtones.

The thematic element of my compositions usually emerges from an impression of some feeling or visionary. Anything from a personal experience, a yearning for something, or a remembrance to simply witnessing an amazing scene of nature and simply reacting to the synesthesia of my impressions. Traveling is another contrast that will summon ideas to come. The simple desire to be transported through music. That will bring it on and get me immediately looking into space for the promise and possibility of music.

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

Once I feel an album and mix are complete, I will listen to it on two different pairs of Focal Monitors in the studio. Carefully switching back and forth between them in certain sections of pieces. Then I do a rough mix and try it on a plethora of different stereos around the house and, of course, the truck stereo. The truck stereo is always the best place to hear whether the mix needs any further cleaning. I listen to the mix on a pair of JBL Bluetooth speakers. Sennheiser headphones. I have a little reading room in the upstairs of the house that has an old Pioneer receiver and a pair of Micro Acoustic speakers from the 70s. If it sounds good on those, then I feel ready to release a project. In terms of my reaction to listening to my own records, It’s always a much easier and more fulfilling experience after a couple of years of finishing something.

I love mixing and seeing a project through to the finish line, but it can be difficult to listen to it again too soon after finishing an album. When listening to test pressings, I have to have the right environment before listening. Either very late in the evening or on an early Sunday morning before anyone else is up. Or while reading a good book. This will keep my mind from responding too critically. However, I am solely responsible for the welfare of my recordings. So, I have to be critical and sensitive to the details I would love for the listeners to feel in my music. After many years of difficult results, I finally have a truly remarkable team of talented individuals who see my records through to the finish line. Harold LaRue is my mastering engineer and post mix engineer on projects I wish to have another set of ears on. For example, he did the re-mix for the “Electronic Voyages” LP release. My masters get cut by the talented Clint Holley & Brian Fanos at Well Made Music. These guys are master craftsmen of the art of making fantastic and authentic-sounding records. My last two releases were pressed by Citizen Vinyl. Always extremely pleased with the results. Silent pressings and full-frequency transfers.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

Of course, there are times when it’s just not the right time to start or work on a project. The one thing I have learned is the art of staying out of my own way. Even after nearly 4 decades of composing and recording music, I still awake every day so excited about music and the freedom and possibilities it provides. No matter what comes and goes in my life, music has always been a constant. However, this is also my career. It’s how I put food on the table and keep the lights on. When constantly being creative is your job, it can prove to be exhausting and challenging. So, I’ve learned how to devote my attention to other things when I need to strike a balance.

Often, I read and get outside. Even if it’s to do other aspects of the work. Changing your environment is vital to keep creative crop rotation. I keep a journal of goals and progress. Small ways to visualize and manifest the things I wish and need to achieve. Being a parent is the biggest aspect of my life. So, spending time and supporting my children is number one. It helps keep my focus and clarity as well. Having a positive routine and rotation of different kinds of work keeps me inspired and looking forward to what’s next.

What gets you inspired?

Early morning silence, hiking and exploring in the woods around where I live. Especially hiking and camping in the autumn and winter. I love thunderstorms and snowstorms. Building bonfires often… Witnessing the amazing evening sunsets and constellations at night. Homemaking, cooking, and taking care of my family. I love reading every chance I get. I carve out as much time with good books as possible. Kindness and laughter inspire me and remind me that we only do this life once: have fun and find the JOY of creating and making music.

I love coming into the studio early with no computer or phone on, sitting down with a strong cup of coffee, and just looking around the room until I begin to visualize a signal path and feel some kind of music emerge. Writing down notes along the way. Then, eventually, that spark happens to realize a piece. What inspires me most is when I see the shape or arc of an album begin to form in my mind’s eye. It just occurs, happens swiftly and evolves so naturally when it does. Albums like “Synesthesia”, “Hypnosis”, & “Muskingum Mysteries” were like that and often inspired by location and the photographs I would take. Just be sitting by a rushing river, a rippling stream, for a few hours. Or walking really old bridges and towns. Or just standing in a hollow witnessing a most beautiful sunset. It’s just like that, and a myriad of ideas will just surge through me. There’s really nothing that compares. When I hike or travel, I take a backpack with me with everything from Music staff paper to frequency charts, to modular patch sheets and will spend many afternoons just recording the information I hear and feel around me. Often quantizing it to the nearest musical value for orchestral temperament. In fact, “Hypnosis” was recorded outside on the back porch of an old cabin I stayed at during my birthday last October. Only using a Sansui 4-Track reel-to-reel recorder. Taking breaks to warm my hands by the fire and going back in to carve out what that record became.

Again, it all continues to confirm my joy and faith in MUSIC. All the stuff that comes after is just how I choose to channel it through and create a humble and honest impression. I will add that I am always much more inspired by projects where all I have to do is program modular synthesizers and roll tape. Mixing in the moment, playing melodies and solos with my hands. I grew up working with my hands, being a musician and audio engineer. I can see the music clearly outside the windows of my studio and in the feeling I have about any particular musical space I am in at any given moment. The computer is a remarkable tool, and I am glad that they’re here for certain things. However, it will never be my brush, palette, and canvas. There’s no better feeling than hitting “record” on a tape machine, watching the tape roll, levels, and the clock counter, knowing full well you have to commit to the journey ahead. Much like life itself, tape and time run out. It’s up to us to find that epicenter of intent over the content and just give our best impression of the musical expression coming through. The joy of creating an electronic wilderness for my listeners to get lost and found in. It’s a beautiful circulation I am grateful for every time.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

I wouldn’t want to be placed in the position of a music critic. It all totally exists. I do listen to lots of modern music, yet only a small number of artists would fall firmly under that category. I’m just an artist who’s been doing their own music for nearly 40 years on their own terms. Simply being in love with the process and circulation of music and sound assemblage. My thoughts are usually focused on what I wish to do next. Keeping open to those possibilities. It’s great to see such a wide variety of people creating electronic music in the way that they wish. It is still the most liberating form of modern music. There are still no rules – let’s hope it stays that way for as long as possible.