Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

I really wanted to play the violin rather than the piano, so I played an imaginary fiddle using stuffed animals. The piano seemed contrived because a single gesture, pressing down a key, produced the entirety of the sound. I was attracted to the violin because it allowed me to control the sound in much finer detail. My parents bought me a violin and got me a teacher. It was my first musical love.

I started playing around with computer music just about the same time. I was fascinated by music tracker software. These very early sampling and sequencing packages ran entirely on a PC, no hardware gear required whatsoever. I still have the project files from those early days. My first childhood composition goes through five sections, each at a different tempo, in under two minutes. I ended up developing that very same type of structure on my new album, but now I know how to make a voice carry over across different tempo sections and I’ve learned a thing or two about making better sounds.

I can’t say I was otherwise exposed to electronic music. My parents had a modest collection of classical and folk music, but one record did stand out: the ballet score “Messe Pour Le Temps Présent” by Pierre Henry. “Psyché Rock” combines sampled sound with rock guitars and Moog bleep bloops. I still love that record. I was making strange sampler tunes on the computer, while still studying classical violin at the Conservatory, then switched over to playing saxophone in a marching band and soon thereafter was exploring parties in the burgeoning local rave scene.

Once I heard Daft Punk and The Prodigy, hardcore and psytrance at the local rave parties, I was hooked on synthesis. I was desperate to learn how the heck these sounds were made. But I still didn’t know what a synthesizer was! I got lucky and found a few nice bits of gear from the local pawn shop: a Korg Poly-800, a Casio CZ-1000 and a Roland ProMars MRS-2. I didn’t have a mixer or multitrack, so I would basically sample short notes and phrases to use in the tracker software. A highlight of these early days was finding a Roland TB-303 and Roland TR-606 at rock bottom prices, just like in the legends you hear from those days. I don’t have any of that gear with me from my teenage years. I ended up selling everything to go travel the world for a year, between high school and university. It was a formative experience that had just as much impact on my development as a musician as did my early experiments with gear and software.

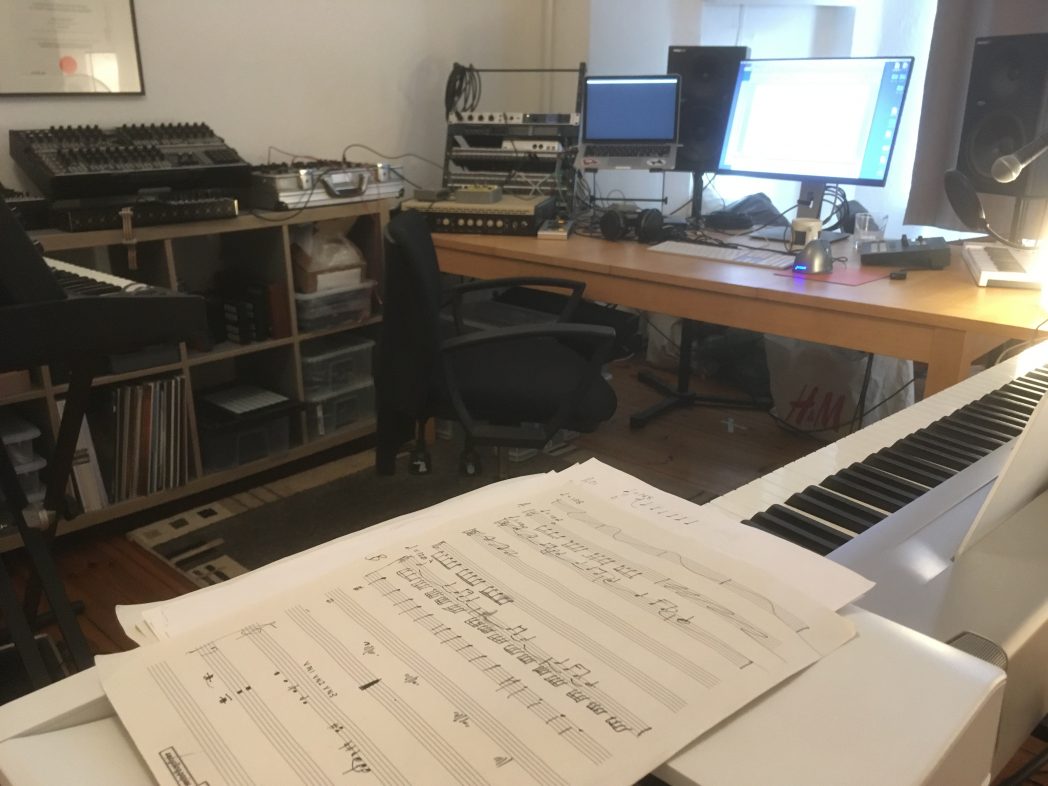

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

I’ve been through maybe five major studio iterations in the past 25 years. My studio setup has always been based around a computer. The first major bit of hardware gear I got was a Kurzweil K2000, I still love it, there’s nothing quite like the wave wrap and the bandpass filter in there. I then tried out a few software-only approaches, especially when I studied classical and electroacoustic composition. During those days I worked with scoring software, Logic for recording sound and Max/MSP for processing audio from scratch. I ended up building my own rhythmic morphing sequencer and swarm resonator. I’ve tried all sorts of analog and virtual analog hardware since then. The big lesson I’ve learned is that every single instrument has its purpose, every instrument has its own character. It’s never a question of which synth is better, it’s a question of which synth will deliver the vibe I need for a specific composition. The right tool for the right job, and the jobs are tasked from a place of purpose. The composition and production techniques, the tools I use, these follow my intentions as an artist. I choose gear that serves my purpose as an artist, to express each component of the vision.

Tell us about your favourite piece of hardware.

I can’t choose a single piece of hardware as my favourite, each bit of gear serves a different functional and emotional purpose. I fell in love with the sound of the Metasonix F-1 guitar pedal at one point a few years ago. I ended up making a couple of albums more or less entirely from the sound of distortion artefacts. It’s an extremely limited device with only two controls. If you don’t plug anything in, the pedal generates an otherworldly screeching sound that you can play like a feedback instrument. I would sample that and use it as a melodic instrument, resample the result through the pedal for textural layers, run the whole thing through a Vermona ReTubeVerb for a sense of haunting nostalgia.

The Noise Engineering Loquelic Iteritas is featured all over the new album. The sound is just something else, a real snarling beast. The amount of overtones it can make, the raw sound, it grabs me and won’t let me go. Nearly every synth line on the album is basically overdubs of the Loquelic, processed and layered. Back in the day I would record many takes and choose the best. That was always such a tedious process. Now I simply layer all my takes and smash them together, moving them around in the panorama and sculpting the aggregate spectrum to make it work. It’s a lot more fun, it throws in a challenge of unpredictability for both me and the listener. I don’t review my takes before putting them together in the edit, I make it work in the mixdown which I do simultaneously as I perform and record.

Finally, a special mention goes out to Erica Synths, Squarp and Endorphin.es. All three manufacturers are making incredibly high-quality instruments, extremely forward-thinking each in their own way. Erica Synths make a series of analogue tube processors, like the Vermona and Metasonix, these are for me some of the warmest characters I can find. Their approach to step entry programming, the Drum Sequencer, is a very clever approach. Finally, somebody made a 4×4 grid. Squarp make the Pyramid sequencer. It is literally the only hardware device that properly supports both polymeters and polyrhythms. There is so much confusion in the music technology world about these two techniques, the words are often conflated. The tracks on The Upward Spiral change tempo and time signature all over the place, and they also have unusual tuplets like 7:6, 8:7 and 9:8. I can compose these tracks manually in Ableton Live, but without the Squarp Pyramid, there’s no way I could perform, let alone improvise, these types of rhythms live. Finally, the Endorphin.es family of Eurorack modules is another set of priceless tools. Their Furthrrrr Generator is another rich tone source I could not do without, and the set of reverb algorithms they made for the Grand Terminal module is itself one of the main sound sources on the album. Near the endpoint of the title track The Upward Spiral, the choir of harmonics is exposed simply by running the raw oscillators through the Endorphin.es reverbs. The reverb brings out the harmonics so prominently in the reverb tail that it sounded to me like a new layer of choirs emerging in the background. Subliminal, ethereal.

And what about the software that you use for production?

The software arsenal has not changed so much in ten years, it’s pretty much Ableton Live and Max/MSP. Ableton Live is excellent not only as an editing and composition desk, its main strength is the fact that I can route audio in and out of the computer at any moment. Developing a composition is a seamless process between laying out audio material, processing the material with external gear and recording improvisation layers back in the timeline. Max is the holy grail of audio and MIDI processing, especially since the integration into Live. The problem with Max was always that it lacked a strong framework of traditional music, working with a regular pulse and musical time was always thorny. Turns out that Ableton Live is quite handy with that approach, and now the bridge is complete between traditional writing and computer music.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on and do you think one day you’ll have it?

I’ve wanted a Haken Continuum for years, there’s nothing else that can give you continuous expressive control with a physical surface. I would love to have a harpsichord at home, oddly enough it’s an instrument that offers the radical opposite level of control but I just love the sound. Part of my musical mission seems to be about reconciling opposites. I also need a new violin. I would like to experiment with Sequentix Cirklon as I believe they started implementing support for polyrhythms as well. So many things to do, so little time.

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

I approach sound design in three ways: textural, spectral and functional. These three approaches to sound design roughly correspond to three types of listening: causal, reduced and semantic.

Textural sound design is about reprocessing a stream of sound and mixing the different versions together. It’s the broad strokes, the most obviously apparent layer of sound, easily perceived consciously. At this level I’m still concerned with melody and rhythm, I create new layers that emphasize the musical content, I use sound design to lean into the rhythms and melodies.

Spectral sound design is about reduced listening. I reduce my perception to a much shorter timescale and I focus on the frequency domain. I listen to the components of a complex sound and make a decision about which of those components serve the artistic purpose and which don’t. I tend to rejig the spectrum of each sound to make sure there’s no trivial resonance masking the important bits. In other words, I get rid of the nasty 6k sine tones baked into every 606 hi-hat sample before that sound gets to roam free in my composition landscape.

Functional sound design is all about the body. It’s the intersection of the physiological and cultural. Different ranges of the audible spectrum elicit different reactions. Even though we all hear differently, there is a range within which we know how most people react, and that’s where the most effective sound design decisions get made. The metaphors we use to describe sound are telling. Whether it’s a punch in the gut or hitting the chest, talking about a deep bass or exciting presence. All those phrases can be mapped to very specific regions of the spectrum. It’s no coincidence that the 909 bass drum has enjoyed such longevity, it hits a psychoacoustic sweet spot between 120 and 135 Hz. You can partly borrow the feeling of a 909 bass drum by imposing a similar spectral profile on any other sound. You can invoke the feeling of an 808 Miami bass by provoking a sustained resonance on any sound. The expressive characteristics of any sound can be extracted and reapplied to any other sound. These sonic signatures are cultural tokens, they provide a link between cultural connotation and physiological response.

The most well-known frequency band is the pain region from 2 to 4 kHz, but every region of the audible spectrum has its own special power. I’ve discovered that sonic signatures are very effective, they can be extracted from one sound and applied to another. Another principle I work with is about volume and loudness. I’m very curious about the limits of audibility and tolerability, if my tracks are to be played at over a hundred decibels, I want to make sure that it gives the impression of being overwhelming, without actually overwhelming the audience’s hearing apparatus. I want to blow your mind, not damage your eardrum.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

Yes, absolutely. The entire album is a catalog of metric modulation explorations posing as dance floor bangers. Metric modulation is a relatively recent development in music history. The most primitive seed is the hemiola, a rhythmic figure in the Renaissance and baroque where a ternary rhythm is briefly interpreted as binary or vice versa, triplets versus binary pulses. Stravinsky took rhythm to another level and kept things groovy. Modernist composer Elliott Carter mapped out the technique throughout his career but unfortunately, he subscribes to hardcore modernism where any regularity of pulse or melody is strictly forbidden. Prog, metal and math rock eventually got involved, but they also mostly kind of fall in the trap of impenetrability. The mind-expanding techniques are all there, but too many are shoved together in close succession for anybody to appreciate any single one. It all kind of washes over you like in modernist music, too much too fast. Part of the brilliance of Steve Reich and Philip Glass is that the structure is exposed at the surface level. That level of transparency in the discourse is what attracts me to minimalism, more than the simplicity of the melodic and rhythmic fragments. Honestly, I am always listening to the structure behind the sounds just as much as I am listening to the sounds themselves.

Somebody once said talking about music is like dancing about architecture. He was wrong. Music is most definitely a vehicle for ideas, both musical and extra-musical. If we are not able to say what ideas are contained in music and in what way the ideas are valuable, that should be taken as an alarming shortcoming either in our abilities to identify value or a shortcoming in the music itself.

So that’s where my mind was around the time I wrote The Upward Spiral. I’ve been sketching out metric modulation and polytemporal ideas for a few years. I slowly figured out that it could work for dancefloor music. Tempo and structure are some of the last formal parameters left for us to explore in popular electronic music. The history of new genres in Western music typically follow a similar pattern of ever more complexity until a threshold is crossed and the fundamentals are no longer recognized. The classical example is the emancipation of dissonance from Bach to Schoenberg. What took 350 years in European classical music took about 70 years for jazz, from blues to Sun Ra. The same process kind of took place already in dance music in 20 years, from disco band music to Autechre asymmetrical perfection on Confield. Tempo is the central parameter of dance music, not harmonic consonance or rhythmic complexity. A similar process happens within club music, where the styles get harder and faster before slowing down again. That happened with hardcore, techno, gabber, psytrance in the late 90s and early 2000s, then electroclash and minimal swept in as a radical slowdown countermovement. It looks like tempo, the speed at which we’re synchronizing people, is the fundamental parameter of club music.

So right now a new generation is reviving 90s techno, which is rather exciting for me as I grew up during that decade, but there’s no way that I’ll participate in straight-up surface-level nostalgia revivalism like we just went through not so long with 80s revivalism. Let alone the fact that techno is supposed to be about futurism, which is antithetical to nostalgia. The 20th century was the century of timbre, we emancipated recorded sound from the underlying composition, sampling changed the game, but the 20th century is also the century of memory and repetition. Revivalism is generally reactionary on its own, and dangerous when masquerading as innovation. I certainly embrace repetition and variation as a great dichotomy, a fundamental music dynamic we know and love, but I absolutely need to find bridges to new territory, from the familiar to the novel.

Let’s get abstract about dance music tribalism, just for a moment.

Dance music is about synchronizing a group of people. People are literally synchronized when they dance at the club. Dance music tribalism is about synchronizing a group of people in a specific scene. People are synchronized metaphorically through their enthusiasm for a scene. Enthusiasm is manifested through the attachment to various aesthetic codes. Unspoken collections of aesthetic codes are embodied in venues, fashion, graphic design, styles of dancing, and of course the musicological qualities of the music itself. Think about techno and it’s quite obvious, stereotypically so, how techno is manifested across these different disciplines.

So a scene works when people identify with these codes simply by virtue of paying attention and participating. People participate by paying attention and reproducing the codes across the various disciplines. Fans participate by paying attention online and at events. Musicians participate by reproducing the musical codes. Belonging to a group is a fundamental human need, but a group can live if it grows, a musical code can only grow by introducing variation. Artists can propose variations on the set of codes, but if you go too far, you challenge the fundamentals and you lose the connection to a scene.

See for me, I noticed years ago that electronic music tribalism seems to put an exaggerated emphasis on tempo. More than anything, more than the quality of the sounds, I just kept noticing that people seemed so keen to define their musical identity and group membership based on tempo. You’ve heard these conversations where DJs and fans wax poetic about the finer merits of 128 versus 132 bpm techno. People seem to be attached to a very narrow range of tempo, sometimes even a specific number. I’ve always found that very curious. I now understand that this tempo orthodoxy contained a clue to propose bridges, portals between boxes.

Metric modulation is what I found to branch out from the nostalgia snake eating its own tail. It’s a technique to create portals between genres, portals between tempo tribes.

The technique consists of changing the temporal perspective. A polyrhythm is about playing two different pulses against each other. Like playing four synth notes against three bass drums, you’ve heard that polyrhythm a bazillion times in club tracks. Metric modulation consists of flipping the perspective, where the four synth notes become the basic beat, and then introducing new parts in that new context. Let’s take the title track The Upward Spiral in my album for example. The track is two parts. The two parts are connected by a riff which always plays at the same speed. The riff is interpreted as dotted eighths in the first part, that’s the classic four synth notes against three kick drums. The riff is interpreted as quarter notes in the second part, that’s a synth note on every beat, as four-to-the-floor caveman rave as can be. But to avoid the painfully obvious I use a syncopated kick drum pattern. The breakdown between the two parts is where the magic happens. During the break, the synth plays on its own, in the absence of a beat the tempo is undefined. A tempo change does occur at the drop, in a 3:4 ratio, from 129 bpm to 172 bpm. Once we have gone through the portal, new drum patterns are introduced that make the 172 groove explicit. The instrumentation is very simple, just a synth, a kick drum and a hi-hat. But I make sure the surface level, the sounds, are evocative on their own. That’s where the production quality and sound design are relevant. That’s my challenge, to make sure the surface sounds are directly emotional, which the structure underneath is rational, the two domains together create meaning and purpose. It’s logos and pathos. And of course, ethos is the proposition I’m delivering right here in this interview.

Each track on The Upward Spiral contains at least one of these tempo portals, sometimes several. I specifically asked Overlook, one of my favourite drum ‘n’ bass artists, to remix The Upward Spiral. I often use that track to segue from techno to drum ‘n’ bass and I wanted to hear his take on it. I am always on the lookout for artists who are experimenting with rhythm, meter and tempo, the whole crew around Samurai and Horo records is really future. Love what Lemna puts out. I asked Sam KDC to get involved and he delivered a cutting-edge rhythmic take on his “Nexus” remix. I was tipped into a rhythmic future organically emerging when I came across Deapmash a couple of years. And then, of course, you get Arca cavalierly smashing across the tempo grid, collage style. Love it. Back on topic though, the tracks on my album modulate between tempo and rhythmic archetypes associated with various genres as a means to metaphorically connect musical tribes. I call them portals.

“Nexus” is a tempo scaffold between EBM, techno, and jungle. The melody remains at a constant pulse and travels through the portals to new tempo lands. The sound design remains consistent across the sections, a constant glaze of direct sensorial experience.

I make a fundamental distinction between sound and structure. Music is not only the language of the soul, music is also a vehicle for ideas. Precise ideas about reality, about society, can be abstracted into musical structures. Musical sounds, acting as they do on a shorter timescale, are perhaps the component of music that speaks to the soul. Musical structure, by definition only perceptible on longer timescales, is the component of music that can most strongly model ideas about the world and society. People are the most valuable emergent phenomenon of the universe, time is the most precious resource we have available, music is about organizing time in a beautiful and meaningful way, and so should society be about organizing people and time in beautiful and meaningful ways to promote growth, effective arenas to challenge ideas, beauty and the creation of knowledge. Life.

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

My live setup has changed for every show. I started building a new instrument from the ground up earlier this year, based on modules from Erica Synth for tones and traditional techno step sequencing, Expert Sleepers for interface the computer and modular synths, tubbutec for microtuning (many of the tracks on the album are microtonal), Endorphin.es for more tones and effects, Squarp Pyramid for sequencing. The Pyramid is crucial for playing and improvising with the metric modulation techniques described above. The plan was to premiere this new approach live at the Kontaktor Festival in May 2020 but of course, that was postponed because of the pandemic. Right now I’m wrapping up new projects at the intersection of music and social change advocacy. The plan is now to get back into the live performance instrument later this summer, after rearranging my studio and a long break to catch my breath.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace and what would be a particular element that you would improve on?

The physical disposition of the workspace must follow the expressive requirements of my body. The workspace is a musical instrument. The same way a large church organ is set up to allow the performer to access the controls in a way befitting the musical language, my studio is set up to allow a musical flow between the tasks. That comes down to where cables are stored, what machines are permanently plugged in, how much desk space is kept free to allow me to crouch on the desk if I need to tweak a synth, how much space is available on the floor to lie down, listen and close my eyes. Some synths are higher up so I can stand up. I wish I had a motorized desk so I could change the height of all the instruments at all times. If dance music is about connecting people through their bodies and feelings, I better make sure that my creative process is also tuned in to my own physical movements. I had serious problems with tendonitis when I was playing the violin and later with the computer. I saw a physiotherapist for a while in music school. I learned about how my body works and some basics of anatomy, simple things like how the bones in the forearm twist and pinch a bundle of tissue, and small details about how I move my arm can have a significant impact on how my entire body feels after working in the studio for hours on end. I solved those problems years ago, it changed how I carry my body when I work at the computer.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

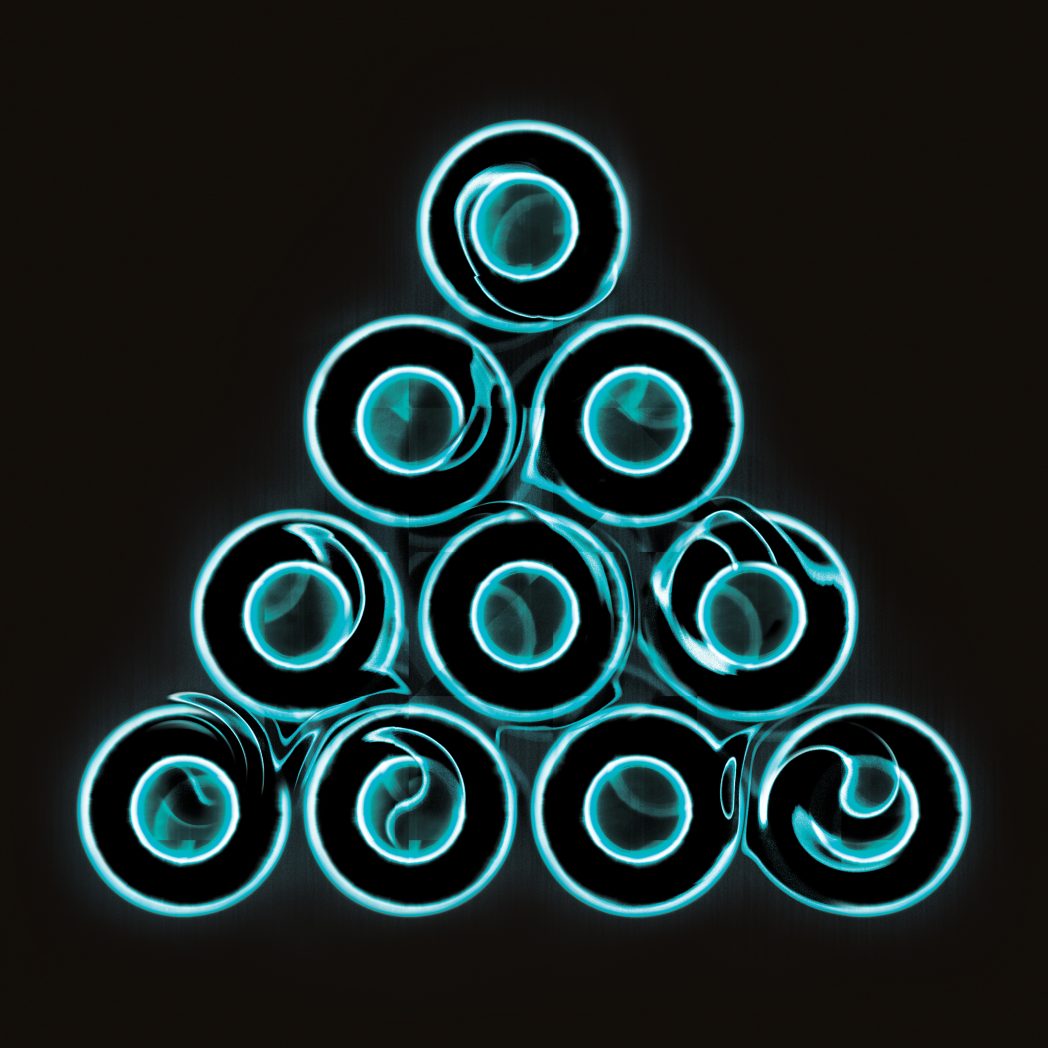

I need to identify three clear goals for each composition. I need to develop a new technique or process, I need to express a personal issue, and I need to express a position on a societal issue. Craft, personal and social. The Upward Spiral, for example, is about methodically mapping out how metric modulation can be applied to club music. The album is about resolving childhood trauma. The artwork is based on the earliest nightmares and waking hallucinations I experienced as a child, and the earliest emotional highs and traumas I experienced around music. Lastly, the narrative arc and titles refer to an outlook I wish to share with the world, the story starts off in the rough sonic world of techno clubs and proposes optimistic and positive pathways, a wholly intentional contrast between the sounds typically associated with confrontation and an outlook proposing earnest growth and flight. Overall, my work aims to translate the immaterial to the material, translate literal intentionality into a language of abstract emotional. The Upward Spiral is about multi-dimensional synesthesia, creating connections between seemingly distinct domains of knowledge.

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

I audition the results the same way I audition the process, using my ears. The piece sounds exactly the same after it is complete as it did a moment before completion. It wouldn’t be complete if it didn’t sound complete. I work on it until it’s complete. A piece is complete when it can do what it sets out to do. When I listen to my music in a different context, at a club or in a living room, I am paying attention to the people. I am listening to music through their ears and their body language.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

Yes. I procrastinate. Procrastination is based on fear. I find myself trying to escape reality, which is, of course, impossible, the reality is that life is right now in every single moment. The only way out is through, writing in my journal about the exact present moment is one of the most effective ways to escape the mindloop. I look inside and I identify the reason I am procrastinating, I identify the unspoken dialog in my head, which voice is protesting the work, which memories and emotions are associated with the resistance, I provide solutions to quell the voice, write it down, this all happens in less than a minute. Identifying the fear and motivation behind the procrastination typically assuages the voice and provides a pathway to action. Another way to escape the mindloop is discipline and habit, for many years I worked on music immediately after waking up, between 30 minutes and 3 hours every morning.

What gets you inspired?

Making the world a better place. Expanding the field of knowledge in music and composition. Gaining a better understanding of my own mind and motivations.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

Popular electronic music, especially club music, is largely defined by tribalism. Musicological and production techniques are subordinate to the social phenomenon. Few artists work on a fundamental or semiological level of writing techniques. We lack vocabulary and a habit of naming the values represented by artists on stage, in the DJ booth, on social media. We have a too poor vocabulary, shoehorning an enormous variety of roles into the words DJ, producer, artist.

The music scene is much more about the scene that it is about music.

Olle Holmberg has been doing extremely interesting work with microtuning, polytemporality and free temporality, while keeping things groovy and fit for a party. Nicole Moudaber is doing very interesting things intersecting festival-friendly music aesthetic with explicit social engagement messages on social media. Arca and SOPHIE are making some of the most exciting music that pushes forward the popular music lexicon, their seamless incorporation of acousmatic structures is something I wish I had started doing when I finished school a decade ago but I just didn’t know how! I love it, so full of hope and inspiration. I sometimes go back to read the correspondence between Stockhausen and Aphex Twin, they were both onto something. They argued for their respective positions of orthodoxy, but Aphex Twin’s last response gives us a hint to the solution. The solution is both! Not only radical repetition, not only radical asymmetry, let’s figure out how to use opposites simultaneously. And I do believe that is happening already.

The potential vocabulary of electronic music is stunningly vast, it’s curious that we exploit so little of it. That’s how it works, to make a popular vocabulary we need to keep things simple and understandable by a large variety of people. That’s what attracted me to techno in the first place, as opposed to working in electroacoustic music or research, I want to map out and expand colloquial musical vocabularies.