Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

I wrote tunes in rock bands in high school and college on various instruments: drums, guitars, and violin. I only started putting notes to paper toward the end of my college career. My violin teacher gave me Arvo Pärt’s “Fratres”, and it was the first piece of classical music that felt really close to what my own voice might be. That jumpstarted me. As for first gear… Age 3: A Rice-A-Roni box with a ruler taped to it. That’s how they would start kids off on violin. It’s maybe a year just learning how to hold it and proper posture.

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

Since I was 22, I’ve always lived in the space that holds my studio. So, the iterations have been when I was forced to move. I did 13 years in a three-story illegal loft in Greenpoint, a few years in a shared duplex in the South Bronx, and then the last 11 at my current spot in BedStuy, Brooklyn. My one financial goal was to buy a place, so I never, ever had to do that move again—which I did.

Tell us about your favourite piece of hardware.

Oh, for the first ten or so years of composing, I would have said my Mark I Fender Rhodes, but now I sit at my Yamaha upright almost daily. I should say my violin, but I won’t for the same reasons you take your parents for granted when things are going well. I mean, I don’t, of course, but you might. And while we’re at it, what’s with all these answers to this that say some sort of black box with jacks? Everyone knows you need to be able to really, really touch things to truly love them. You can only really love an instrument, come on.

And what about the software that you use for production?

The software that gives me the deepest psychic payback is using Time Machine for backups. I wish I had done it more. I am also quite fond of the software instruments I make that let me play multiple lines on the violin and drive synths, among other extended moves.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on, and do you think one day you’ll have it?

No, but people want my gear! Once, my ex left the gate open while I was on tour, and some dude came into my studio and stole a bunch of gear. I got a DM on a layover in Reykjavík from a stranger who said they had bought all my stuff for like $15, stayed up all night on cocaine, going through my hard drives and Googling audio file names to figure out who I was. True New York story!

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

I think much more about orchestration than about layering up samples or whatever people do. I start with great instruments and then mostly leave them be. There is nothing more insufferable than clicking through a sample library. Just go work for the IRS. If something isn’t sounding right, 9 times out of 10, it’s a problem with the arrangement itself. Fix your composition. I record all my solo albums without overdubs, so the song is as good as I wrote it and play it, and both of those are life’s work to get great at. I then leave, making the sounds really shine and shimmer, but everything is pretty far along by then.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

I’m always trying to do more with the expressive capabilities of the violin, especially as it intersects with live processing. The range of the fragile, crystalline effects on this record is side by side with big, thick, processed double stops and lots of angular melodies that lift and spin. Compositionally, I’m always trying to push harder too. There are wild, 13-minute multi-section journeys beside 1-minute miniatures on this record. It’s all about playing with scale.

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

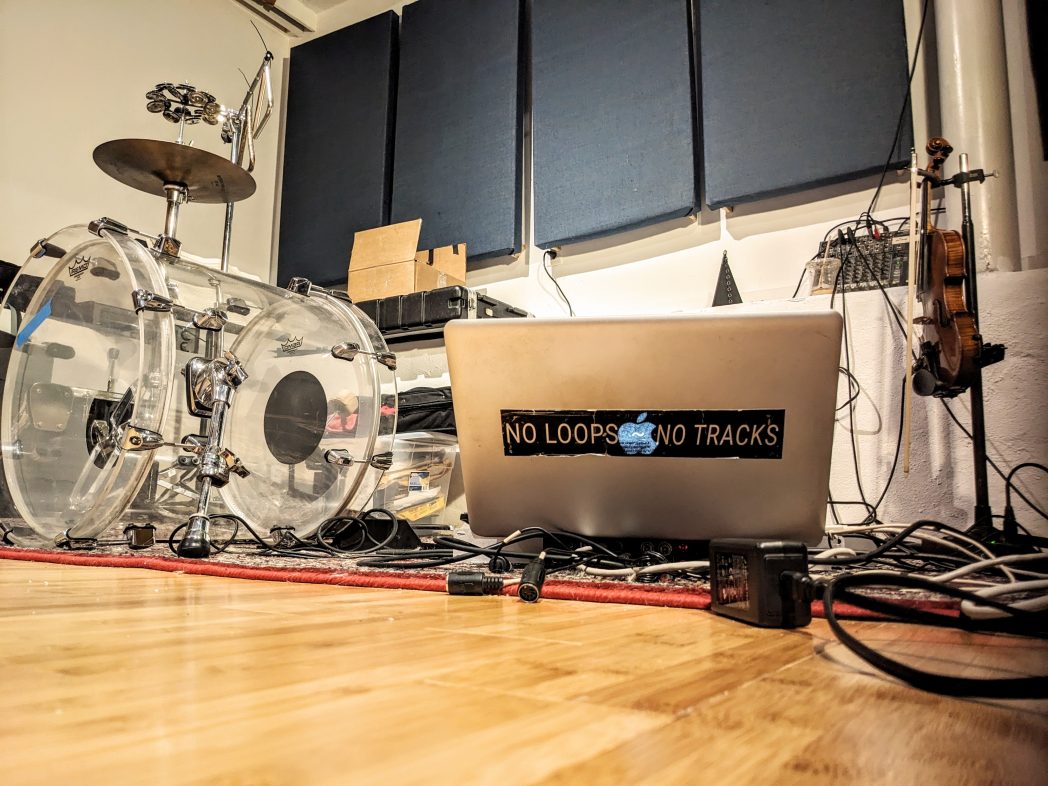

My live setup is my violin and a kick drum with a trigger plugged into custom software I run inside Ableton Live. It’s an extended instrument where I’m always playing, but Ableton is never “playing”, just processing. The computer stays on the floor. I stand and play the violin, my feet working the kick and an octave pedal board. I’m also quite fond of tuning forks processed through the bridge of the instrument to create new, unfurling melodies from that single pitch, but not on this record.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace, and what would be a particular element that you would improve on?

The most important aspect is the isolation and permanence. I can remove myself from the world and do me, and it’s always 100% set up and ready to go. The barriers to getting to the making are as low as possible. It’s important the space isn’t too “precious”; it’s a workspace, not an arboretum. The space is modular, and I can set it up how I want. It has a pole in it so Rachelle can dance to my music. It’s a space to look inwards, to focus your emotional life into a performance. Improvement? I should really clean that bathroom…

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

An idea will start from playing the violin or the piano. It could be me messing around with an effect I’ve made for my live setup. It could be an intriguing way a chord on the piano leads its voices down into a new chord. From there, we see where these gestures want to lead, looking for a paragraph from these sentences. Then bigger questions about the story start to emerge. What are the other characters here, and how do they interact? First and foremost, composition is about building forms. This works best, I’ve found in this bottom-up manner where every gesture resounds with some sincere purpose that leads to the next moment—a moment that somehow feels both surprising yet inevitable—when things are working. These pieces really require me to deliver a great performance when the engineer hits record: After a couple of years of playing them live and then recording them, the label will take nine months at least to get them into the world. Of course, by then, I’m already on to the next work…

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

It’s typical that I won’t record anything for a very long time, refining work by performing, often through multiple tours, before recording. For other work, I will make MP3 versions and listen on my various not-great headphones and through yet-worse laptop speakers, often obsessively for days. If I’m still excited by it, some smart engineer will be able to clean up the sounds or make sure it works on AirPods or whatever the kids do.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

I’m doing other work. If I’m putting something off, it’s typically because I don’t think I have enough information or stamina to do that thing yet so I’ll pivot to working on something else in the meantime.

What gets you inspired?

Being completely alone at the piano, ideally in the middle of the night, buried in the basement lab when everyone else is asleep. There’s nothing more freeing than a moment where you know you are absent from everyone’s mind. And sci-fi movies.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

I’m quite sure I wouldn’t know the state of the union. It is true that usually when I hear music labelled as such, I can sense a lot of hard work going into the sounds and correspondingly very little currency spent on the melody, harmony, or overall form / flow of the work. These are the things that I think give music its stakes and fuel a listener’s emotional investment, less so how devastating your compressor is. My unasked-for advice would be to start with just making great songs before playing sonic dress-up. This has nothing to do with genre: The reason Brian Eno’s ambient works sound better than yours isn’t because he had access to better sounds than you; it’s because he knows much more about music than you. It’s really just about how you want to spend your time.