Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

My first attempts at composing grew out of improvising. In 1970-71 I was improvising with a shifting bunch of players, playing a cross between free rock and free improvisation, so I started writing lyrics and simple forms that acted as a springboard for improvisation. A lot of musicians came and went – they wanted more structure, more normal – so the group ended up as a duo of myself, playing guitar and flutes, and Paul Burwell, playing the drums. It was impossible at that time to carry on as a duo with any rock ambitions so we slid sideways into the emerging free improvisation scene in London. Both of us carried on composing though. Again, these were simple structures that opened out into improvisation, or they were short songs that I wrote for performance, two of which ended up on my album for Brian Eno’s Obscure label in 1975.

My first piece of recording gear was a cheap mono cassette recorder made by Philips. It had a limiter so if we started a piece playing loud the level would suddenly drop off a cliff. I had no money then so I was buying really cheap tapes, often 120 minutes a side to economise. The quality was atrocious but at least they’re a memory of a particular time.

The next big step came in 1987. I was working as a full-time music critic then and as part of my job I bought two records that made a big impact on me – Farley Funkin Keith’s “Funkin With the Drums” and Model 500’s “Night Drive (Thru Babylon)”. I wanted to be able to replicate that sound but I was also thinking about the necessity to get a word processor for my writing work. The Atari 1040ST with Steinberg’s Pro-24 software came onto the market in 1986 and they allowed me to do both jobs, though I was still going into studios to actually record pieces until 2000 and continue to do so if the situation requires it.

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

Basically three, because I lived in three different places between 1987 and now.

My set-up right now doesn’t look like anything at all, other than a laptop on a desk or my lap, a microphone on a stand, a soundcard, a few different mixers, a cheap little midi keyboard and a midi controller. There’s nothing special about any of it. I’m still writing and researching so any set-up has to be multi-purpose. I’ve got a pair of Dynaudio BM6A monitors which are lovely but I barely use them. My living situation doesn’t really allow for it so I mostly record and mix on headphones. That’s a bit shocking to some people but we have to work with what we’ve got.

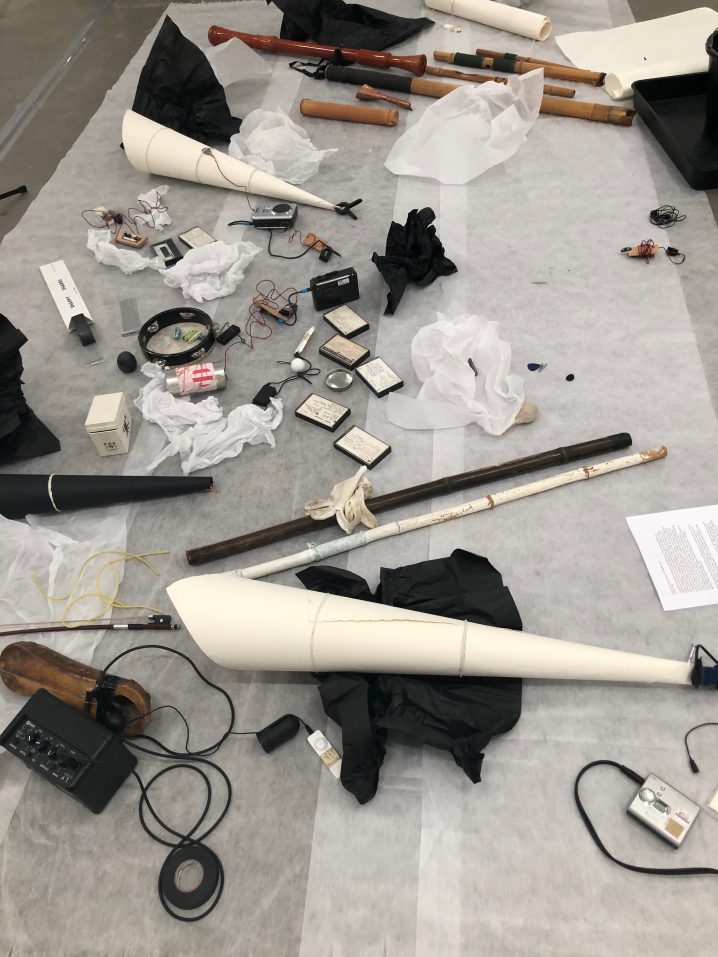

To me, the most important element of my process is my collection of instruments and sound makers that I use, of which there are hundreds ranging from toys to vintage guitar pedals, bird calls, stones and home-made flutes, antique Asian percussion, guitars, bass guitar, lap steel and pedal steel guitars, bass recorder, vibration motors, bone conduction and vibration speakers, paper amplifiers and a big collection of field recordings. In that sense, the studio is dispersed throughout the entire space in which I live and it allows me to continually generate new sounds with which to work. What I use changes all the time as my ideas change, although there are certain things I’ve been using for fifty years.

Tell us about your favourite piece of hardware.

Hahah, see above! If I find a strange audio file I’ve never used before on an old external hard drive, then for about five seconds that hard drive is my favourite piece of hardware. Whatever is allowing me to find the sound I’m looking for is my favourite, at that moment, and then it sinks back into the pack. I used a lot of techniques that are relatively new to me on my new album. For example, I was amplifying tiny sounds with a cheap lapel microphone and also using cardboard boxes as resonators for Ebows on drum snares. That makes what I do sound pretty esoteric but it all comes from experimenting with materials and a lot of that happens in live situations, in front of an audience, so there’s an element of pragmatism to it.

And what about the software that you use for production?

Mostly I use Logic Pro X. I used to use Ableton Live as well but since I stopped using it for live gigs it had fallen out of favour. Then again, it’s nice to go back to it occasionally and create live mixes via a midi controller, recorded direct into Logic as a performance. I’ll also use it if I want a particular effect but that’s quite rare. Something else I used to use a lot was an editing software application called DSP-Quattro. I used it particularly for its pitch shift, which combined with some of its other functions allowed me to generate a huge library of personal sounds, many of which began from quite bizarre origins. By about the third iteration and once I’d given it a fanciful name, like Creeping Into the Room or Spectral Witness, I had no recall of how these sounds had originated. DSP-Quattro had to rebuild the software to adapt to High Sierra. They did a great job but somehow I was in love with the earlier version. I still use it a little bit but also I feel that way of working was coming to a natural end anyway. I try not to fight against changes like that – just go along with it and see what happens next.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on and do you think one day you’ll have it?

Not really. I guess I don’t think like that. Sometimes I buy a new guitar pedal but then I come to regret it when it doesn’t get used much. In the 1990s I used to spend a huge amount of time editing sounds in outboard gear but then I got tired of it and moved on. Recently I was approached by two guys who wanted to issue vinyl editions of two or three of my albums from that period. Listening back to them it struck me that some of the sounds were interesting and unusual but they were very much of that time, working with what I had and trying to get the best out of it. Usually, I try things out first. Somebody I was mentoring sent me a piece they’d made using Celemony Melodyne. I thought it sounded great so I spent some time experimenting with the trial version. After about two days I decided I didn’t need it. In the end, it comes back to an important principle that’s both simple and very complex. If you’re playing an instrument you want to develop a distinctive tone that’s identifiable as your sound. It’s the same with using a computer. Does it sound like you or does it sound like something you just bought and downloaded?

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

I don’t really use the term sound design, or should I say I don’t make a distinction between composing or designing. I try to treat all sounds as equals. The process of making a piece is a question of layering and subtraction and that has similarities and differences from the other things I do, like writing, painting, improvising. When I’m composing a piece I’m bringing together a lot of elements from different sources into the same space so all of those temporalities and spatial dimensions have to work together. Some people would call that sound design but I’d say it’s just twenty-first century composing.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

There’s a track called “Always she seemed to be listening to some foray in the blood, that had no known setting” and that was built from a minidisc recording from the 90s of my old friend Paul Burwell, who is no longer with us, playing bells.

I’d used Flex in Logic for a spoken vocal on a previous album called Dirty Songs Play Dirty Songs and found it really disturbing, almost upsetting in the way it disrupted the voice. I guess my approach to it is the opposite of what was intended, so instead of tightening things up, I’m tearing them apart. When it’s successful, which is not often, it creates really dislocated rhythms and strange artefacts, like ghost notes. I doubt if my way of using it is useful to anybody else, which is why I’m talking about it here. To me, it has the potential to create a completely new kind of music, though not a music anybody wants to listen to right now ☺

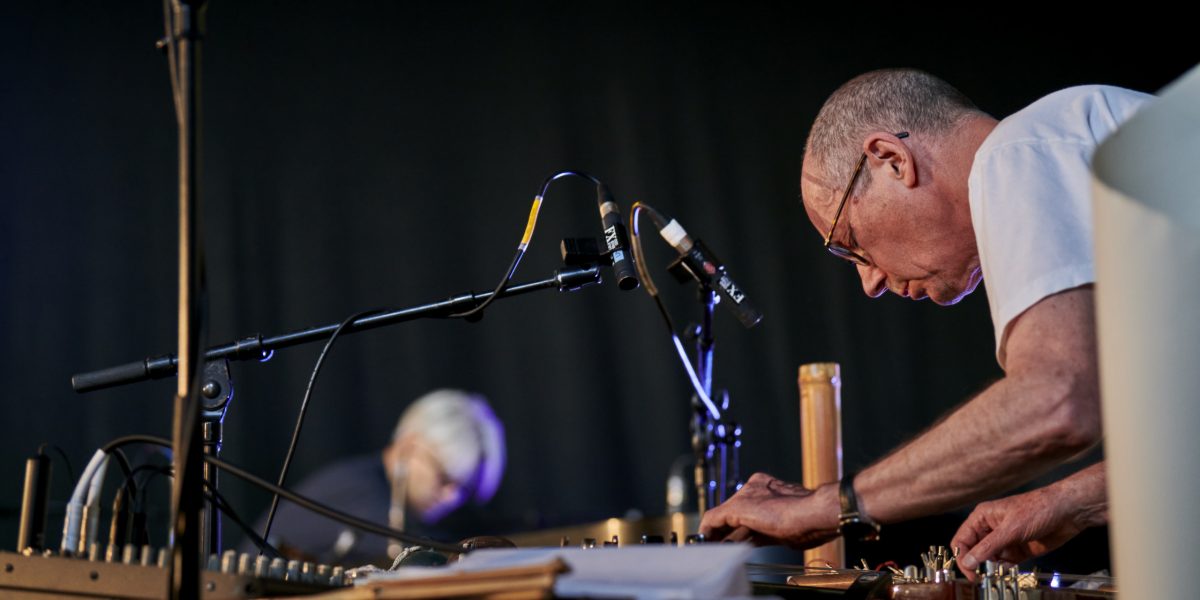

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

Live set-up varies wildly according to who I’m working with, what the situation is, how far I’m travelling and by what forms of transport. It’s sort of practical and impractical at the same time – impractical in the sense that I seem to be carrying a case full of junk. My ideal would be to work with nothing but paper but that’s never going to happen! I’ve been experimenting with low-tech resonators. A cardboard box is great for that because it weighs nothing and you can also put things inside it, so it’s serving a double function in terms of your packing. That idea of economy is very important to everything I do. When people hear paper clips or a piece of paper amplifying voices they can’t believe it – there’s a kind of uncanny magic to it, because the material itself is very humble, very simple.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace and what would be a particular element that you would improve on?

The fact that’s it’s flexible and minimal. If I feel like recording in the kitchen then it’s not much of a problem to do so. In a way that’s a product of current technology, the fact that it’s portable and adaptable, but it also relates back the kind of studio built by Joe Meek, using every part of his living area including the bathroom, or the way that record companies used to travel to a city, set-up a studio in a hotel and then invite all the local musicians to come and record.

I don’t have much space so that’s what I have to deal with. I suppose my dream studio would be a very silent, dark, spacious room with big glass doors that opened out to a view of the kind of Zen garden I visit a lot in Kyoto. If I moved out of London I could probably do it but my work isn’t made from perfect situations or purity. I prefer to deal with compromises and obstacles. It’s more like life.

The point is that I don’t want to be locked into any one way of working because my ideas change from year to year. “Studio” should be a concept of the mind, a place where you can create other worlds. For that reason, I like to be close to change. I like to sit in my kitchen, looking out at the garden, or sit in the garden and I can work on music. If a fox appears, or frogs, or a newt or robin, all of which happens, I want to be able to feel they are a part of my music. If I was locked away in a soundproof, windowless room in which the set-up was always the same, I couldn’t experience those visitations of non-human life.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

Recently, I watched a very funny clip from an interview with Xenakis. His answer to every question was “I don’t know.” Whatever I can tell you about my process of composition is probably an invention. With my new album I know I started to think about titles. I’d be watching a film or reading a book and thinking, that would make a good title. They’d be very long but they’d have a certain atmosphere or feeling so I’d write them down. I also had a lot of fragments, audio files that were experiments of one kind or another. I had a few random influences floating around in my head as well – some production ideas that I’d picked up from Tyler, the Creator’s Flower Boy album, for example – but most tracks begin with a sound and once that’s taken hold and you’re immersed then you don’t know what you’re doing. You follow it to the end.

The one thing I will say is that I wanted to make a record of contrasts in which very physical, rough-textured sounds were thrown into the same pit as string sections and lush chords. That’s an aesthetic decision but it’s also political, to a degree, because it’s a reflection of how we are obliged to live now, surrounded by the luxurious and miraculous but subjected to various forms of violence and crisis.

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

With this album and the previous one, I was monitoring almost entirely on headphones. That’s probably evident because I play around a lot with hearing phenomena and micro-detail. It’s not ideal, though, so I took it to Dave Hunt’s studio, just to check my mixes. I first met Dave at the end of the 1970s. He was an engineer on Flying Lizards sessions in which I took part. I’ve worked with him as a studio engineer many times since then but he’s also collaborated with me on exhibitions, installations, big outdoor shows, mastering and restoring, you name it. I trust his ears and his technical knowledge is endless, plus he has big monitors that are well set up. It was very gratifying to hear the record over his system because we both agreed that only one brief part needed adjustment. Same with Lawrence English who mastered both records. I completely trust what he does.

Usually, I hate hearing my music over another system. The theory is that a recording should sound good over any system but I think we make huge allowances for differences, maybe because we know the music already, or at least know the type of music. When it comes to hearing our own music, which we know intimately, then those differences can be really painful. At least they are for me. I was speaking on a panel last year at Seattle’s PopCon, a really bizarre panel which included Steve Perry from Journey and Ishmael Butler from Shabazz Palaces. They played short extracts of our respective musics before we got talking and I felt totally depressed when I heard mine. They chose a track called “Ceremony Viewed Through Iron Slit”, from a 1997 album, Spirit World. I thought the mix sounded muddy and you couldn’t hear what was going on. Afterwards, Ishmael seemed excited about my track, asking me whether I’d made it on Ableton Live. I had to tell him it was recorded onto 24-track analogue back in the day before anything like Live existed. For me, it was great because I love Shabazz Palaces. It reminded me that what we hear is not what other people hear.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

Procrastination is at the heart of what I do.

What gets you inspired?

Honestly, I don’t know. I don’t even need to be inspired to work. Sometimes I can be feeling terrible for two weeks and then suddenly I start and the making builds up its own momentum. I can get excited by seeing certain films, reading a particular book or travelling somewhere but I wonder how that translates into the actual work? Last year I was reading a lot of speculative fiction by writers of Nigerian ancestry, like Nnedi Okorafor, Tade Thompson and Akwaeke Emezi. While I was working on the Apparition Paintings album there was one particular track that was throwing up a lot of struggle, more or less refusing to allow itself to be made. Suddenly it started to feel completely different and I felt alive. To my hearing, it had the atmosphere of certain scenes written by Nnedi Okorafor, so I borrowed a sentence from one of her novels to name it.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

If we’ve learned anything, finally, from lockdown during the Coronavirus pandemic it’s that we can’t depend on any of the things we take for granted. I’ve been working on curation of a big electronic music exhibition for the past three years and I still don’t know what electronic music is at this point in history. Electricity is just an energy that exists everywhere, not least within the body. I totally understand why electronic music became a genre unto itself during the twentieth century but we’re in a different phase now. I don’t really think of my music as electronic music – it’s music of objects, materials, processes and bodies. If the electrical grid failed tomorrow then it would create huge problems, turmoil, maybe collapse but within that maelstrom, if there was any opportunity to do so, I’d still be able to make music.