Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

First, I was a classical pianist. I studied at Juilliard in New York. I taught at Juilliard for 9 years. Increasingly, I believe that music is becoming more participatory, more democratic. Listeners are not passive now. I’m not sure there are “composers” any more. Sounds are turned into music as each person listens…

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

This is the first album I have done that uses Dolby Atmos. For “Eno Piano,” there were five days of recording sessions at Studio Besco in France. My engineer Martin Antiphon recorded with many mics — essentially an array of 12. During mixing and mastering, all that material was used to allow spatialization, and movement.

Tell us about your favourite piece of hardware.

The Steinway Model D concert grand piano! A relic of the Industrial Revolution, to be sure, and still used to make music today, in many different ways.

And what about the software that you use for production?

From the beginning, we imagined this recording as immersive audio. We wanted to capture all of the resonances that occur in the studio, and inside the piano. During mixing, Ircam SPAT was used to control distances and rotations differently in each piano track. With Eno’s original releases in mind, in “Eno Piano”, there is some slight pitch detuning, and emulation of magnetic tape at certain moments.

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

In Eno’s original production, he sometimes used differing reverb on various strands of the musical texture. We are going farther. In some cases, several virtual rooms are created. So, we hear simultaneously some layers of the music in one room, while other layers are sounding in other spaces with other properties.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

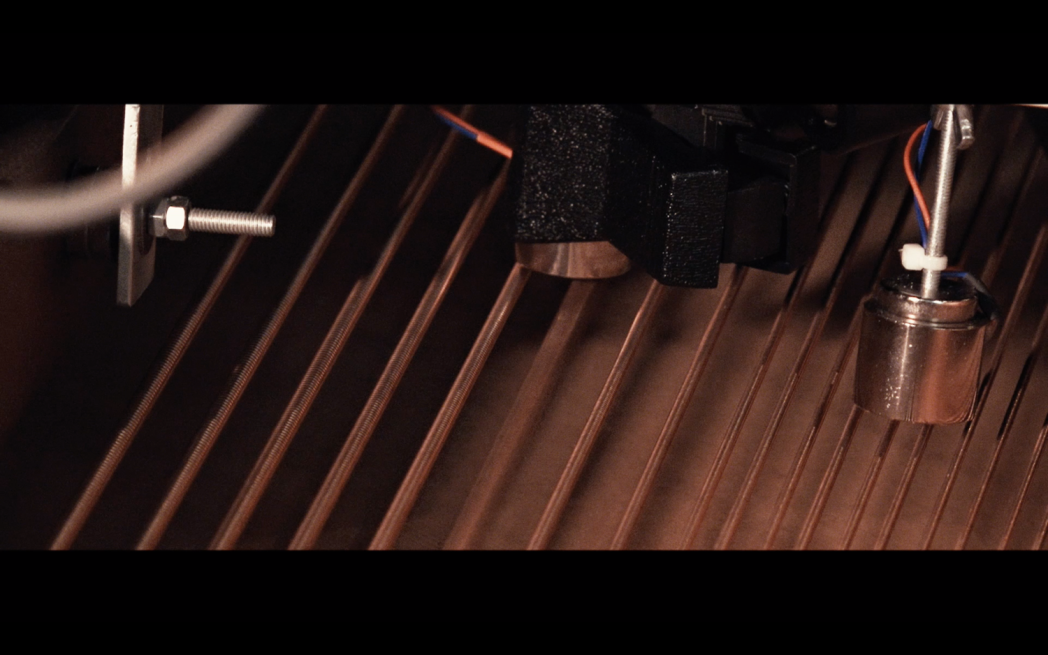

In recording “Eno Piano,” Florent Colautti provided remarkable electro-magnetic “bows” that are used inside the piano. Strings can be made to vibrate continuously for long durations, making musical drones. The bows don’t touch the strings but can provoke precise frequencies, overtones, and ambiguous sounds — it’s hard to believe these sounds are all coming from an acoustic piano.

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

For the live “Eno Piano” shows, I am playing on a large Steinway grand piano, and also triggering clips taken from the album which are overlaid on my live piano playing. In some tracks, I play on a small MIDI keyboard that is connected to a piano simulation that makes long, diaphanous tones.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

Music is around us all the time. Making music is more a matter of selection, less a matter of creation.

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

It’s necessary to accept that a recording will be heard in many different ways. More and more, I want to produce music in a way so that all these listening situations are valid.

What gets you inspired?

The people who listen.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

We are in the middle of a remarkable time for music, and all kinds of artistic processes and work. Technology is allowing us to understand better what human musicians have been doing for a very long time.