Editor’s Note: This is part two of an article titled “Analog Fetishes and Digital Futures” written by Mike Berk from a fascinating book, Modulations, a History of Electronic Music, Throbbing Words on Sound (2000). Republished on Headphone Commute with permission of the publisher, Caipirinha Productions / Cultures Of Resistance Network,

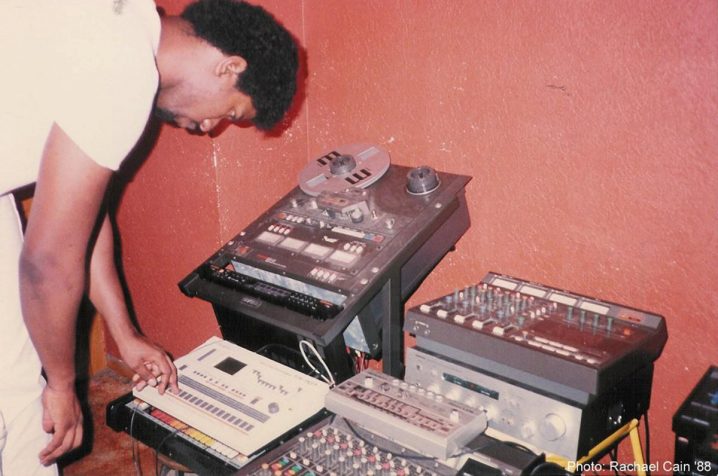

The mid-eighties saw piles of analog gear languishing in the back rooms and bargain bins of secondhand music shops across the U.S. and Europe. In and around Detroit and Chicago, a few enterprising young musicians, in pursuit of new sounds but unable to raise the cash for the DX7s then fashionable among proper studio professionals, turned to the few machines that could be had: TR-808s, TR-909s, and TB-303s from the Japanese manufacturer Roland.

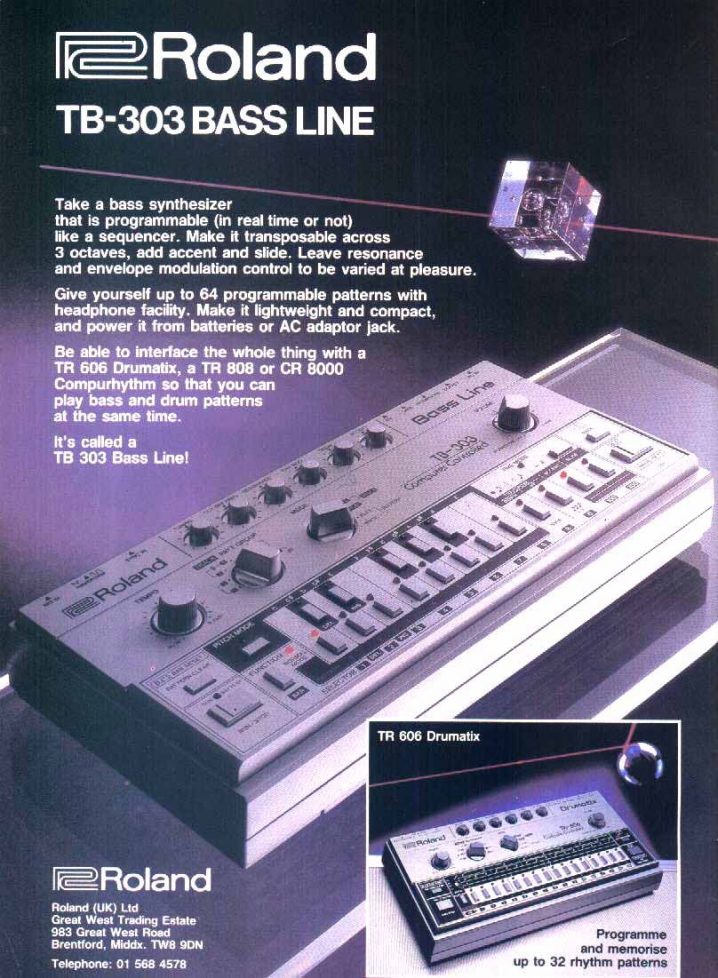

Introduced in 1982, the TB-303 Bassline was originally intended as a portable accompanist for practice situations, demo recordings, and solo performances. The 303 is a stripped-down analog synth, optimized for “bass” sounds and thus offering very basic tone-shaping controls that are hitched to a similarly basic onboard sequencer. One punches in a series of notes on the 303’s rudimentary keyboard, sets the desired tempo, presses play, and waits for something resembling a bassline to emerge. Given that the programming interface is free of visual aids, the process is fairly counter-intuitive, and it’s absolutely impossible to reproduce either the sound or feel of a live bassist. Demand for the unit never emerged, and Roland soon discontinued it.

The TR-808 and TR-909 Rhythm Composers fared somewhat better in their day. They featured an intuitive user interface and a variety of distinctly unrealistic analog drum sounds. The 808, with its deep, resonant bass drum, thin, weightless snare, and ultra-synthetic “cowbell” beep, was one of the first successful, fully programmable drum machines. It was also the first such unit that could store an entire song (verses, choruses, and fills) rather than just patterns. It found its way onto a wide variety of records – everything from Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing” to the first couple of Run DMC albums – and provided the pulse for the electro era. The 909, an improvement on the 808 concepts, features a more aggressive sound overall: The bass drum has a more tangible, thumpy attack, and the snare is punchier. While both machines had been fairly popular, they fell out of favor as sampling drum machines like the Oberheim DMX and the LinnDrum appeared. These new boxes offered more “realistic” sounds, consigning the 808 and the 909 to the budget bins, where they joined their sibling Bassline.

House and techno had found their electric guitars. In the hands of Marshall Jefferson, Larry Heard, Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson, the supposed faults of these machines became strengths. The difficulty of programming the TB-303 accurately made it a very democratic instrument – a novice had just as good a chance of producing a usable bassline as did an expert musician. Landmark Chicago house records like Phuture’s “Acid Tracks” and Sleezy D’s “I’ve Lost Control” – featuring distinctly unbass-like strings of random eighth notes punctuated with accents, a bit of portamento, and some seriously flatulent filter sweeps – made this buzzy, squelchy little box an object of desire once again. Since then, everybody’s used one or imitated one (other Roland synths of similar vintage, especially the SH-101 and the MC-202, can be made to behave similarly) at one point or another. Jeff Mills and Richie Hawtin made the 303 essential to second-wave Detroit techno and the European subgenres that followed. Since then, trip-hop godfathers Massive Attack have even found ways to use the 303 effectively for the sort of slow, elegant basslines that its designers might have had in mind in the first place.

In search of futuristic tones, the Belleville Three (Detroit pioneers Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson, so-named after their high school alma mater) had little interest in supposedly realistic drum sounds, and the resolutely synthy outputs of the 808 and 909 fit their needs perfectly. The four-to-the-floor groove and endless snare-roll crescendi ubiquitous in house, techno, and everything that followed come from the 808 and 909. Both machines are so widely used that it would be easier to list records that don’t feature them than to even think about the immense catalog of those that do. More recently, a number of audio extremists, including Alec Empire and just about everyone involved in gabba, have discovered that the 909’s nasal aggressiveness makes it a potent sonic weapon when combined with distortion from guitar stompboxes or overdriven mixer inputs.

. . .

[Coming up: The Birth of Sampling]