Chris Clark to me by now surely feels like the embodiment of Warp Records’ legacy all wrapped up in one creative mind. His debut, Clarence Park, surfaced in 2000 at a time that Warp was outgrowing its rave and acid house roots and exploring a quite varied terrain, dipping into psychedelic rock with Broadcast while Autechre forged new paths in so-called IDM and experimental electronic listening music. Chris Clark’s knack for sculpting sound and synthesis makes him feel like a kindred spirit to revered tinkerers like Aphex Twin, Autechre, or Mark Bell (LFO), but his restlessness and tendency to amp it up with a more, more, more vibe perhaps feels closest to the first solo album on Warp by Jamie Lidell (released way before Lidell embraced a focus on R&B pastiche); it skitters with nervous energy, chaotic layering, a clear love letter to sonic experimentation.

But what’s made Clark’s music so compelling over nine albums is his unwillingness to stay still for very long. He seems to be an artist for whom experimentation is a crucial part of making, wherein even embracing convention — the acoustic guitar work that informs 2012’s outstanding Iradelphic album, for example — sends his creativity in a new and focused direction. It’s a sharp contrast up against 2008’s Turning Dragon, an absolutely pummeling, raucous techno album that shows off Clark’s more bangin’, rougher edges with style. And yet his most recent release prior to Death Peak was The Last Panthers, a series of cinematic instrumentals that largely eschewed any of the angular form-making and wobbly synthesis that characterizes much of his varied repertoire.

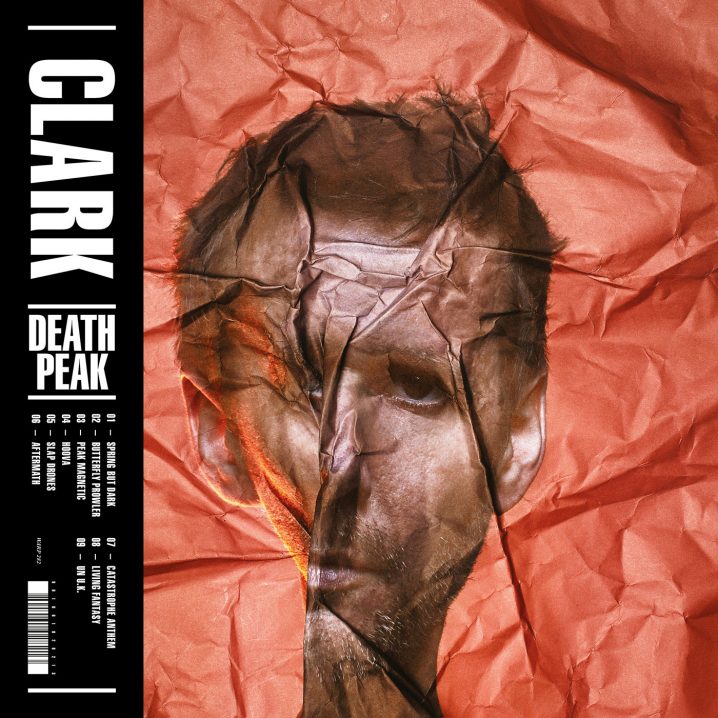

With that hefty prologue out of the way, what then of Death Peak itself? My first impression of it is that it feels like quintessential Clark, and yet it feels more of a hybrid of his self-titled album released in 2014 and the understated beauty of his score to The Last Panthers, each wherein Clark smoothed over some of his more abrasive tendencies and delivered a more polished, easier body of electronica. One noteworthy changeup in Clark’s sonic arsenal is the addition of children’s choir on several of these pieces, beginning with the lilting opener, “Spring But Dark” (an appropriate title). “Butterfly Prowler” is one of the spryest dancefloor workouts to come from Clark over the years, led by a steady four-to-the-floor kick and a warbling, jaunty synth pattern, a trajectory continued with “Peak Magnetic,” a full-on anthem that continues to burn at a good clip.

“Hoova” flirts with rave hoovers just as Clark has toyed with and often turned on their side dancefloor conventions over the years, with staccato vocal bits that recall Holly Herndon’s vocal pointillism. “Slap Drones” again brings the party, with a thick room reverb on everything that makes it feel like a live take as bass synth stabs and crude scrapes of noise propel it forward. But Death Peak takes a turn after these busier, fuller arrangements, and largely bids adieu to the dancefloor as the remaining four cuts explore a headier territory. “Aftermath” glides on airy wordless vocals, hammer dulcimer, and angelic cascades of sonic filigrees and flourishes, before making way for “Catastrophe Anthem,” an oddly appropriate name for the triumphant, soaring and yet dire arrangement herein. The children’s choir comes to the fore with a slightly haunting line: “We are your ancestors,” just as the music expands and swells to swallow the scenery.

The album is best experienced in one solid go, treating it like the mountain climb that it is. Its upbeat beginning and ramp up toward something more climactic, followed by a prolonged denouement into cinematic beauty, it all feels like a narrative that we collectively experience as listeners. For all its twists and turns, Death Peak plays through with immersive ease and enjoyment. In other words: Good stuff as usual from Mr. Clark, another highly recommended album.