Just a few quick words on our new feature, before we dive in… AFTERWORDS is more of a retrospective than a review, conceived by Will Long of the beloved Celer, inviting the reader to spend some time in the company of an older release (one from 1988 in this first entry), and reflect on all the music that has brought us here… Enjoy!

First, some background. The film version of The Beast was released in September 1988, about six months before the end of the Soviet-Afghan War. On one side was the Soviet Army and the allied Afghan forces, and the other side was the Mujahideen insurgents, many of whom later became members of Al Qaeda (for one, Osama bin Laden). One of the most influential turning points in the war was the introduction of the Stinger Missile, used by the Mujahideen – who were funded by US Congressman Charlie Wilson thereby supported by the United States against the Soviet Union as this was the tail-end of the Cold War.

According to William D. Hartung in his article “We Arm The World”, “The early foundations of al-Qaeda were allegedly built in part on relationships and weaponry that came from the billions of dollars in U.S. support for the Afghan mujahideen during the war to expel Soviet forces from that country.” Interesting, huh? This was also directly before the end of the Soviet Union – the end of the Cold War with the United States – at which time Ronald Reagan was president of the US, giving obvious reasons for the States’ support of the removal of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan – likely with the hope to replace it with instead an Afghanistan allied with the United States.

The film itself is also an ironic enigma. The story follows a lone and lost Soviet tank with a Captain Ahab for a commander against a former crew member who essentially switches to the Mujahideen side to hunt the Soviets in the tank where he just came from. It plays heavy off of American stereotypes of Soviets and regardless of this and that the results are somewhat unrealistic, it’s a great film. Ironically, the actors are mostly Americans (Jason Patric, Stephen Baldwin), and despite playing roles as Soviet soldiers, they all speak English throughout the film. You can’t help thinking at the end how strange it seems since the United States has spent so long fighting in Afghanistan some of the same foes that the Soviets did – though the latter actually helped to create them, and that if you ignore the uniforms, it becomes more of a protest film against the United States’ war in Afghanistan rather than a protest of the Soviets in Afghanistan. Wait, is that confusing? Anyway, it’s a different story, but interesting nonetheless.

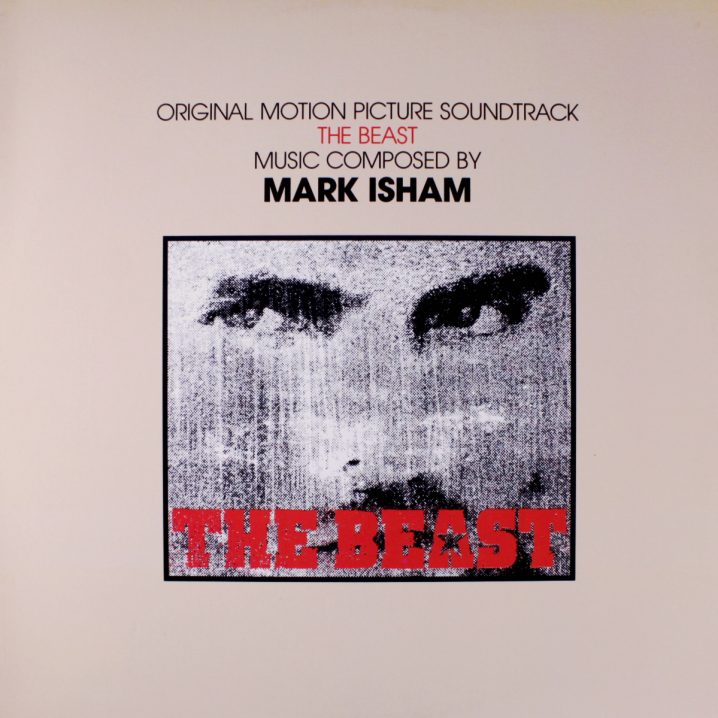

Finally, about the music. The score was made by Mark Isham (who made the excellent score for The Hitcher 2 years earlier), and there are all the obvious signs that it was made in 1988. There are lots of gated fx drums, desert-drenched solo guitars, synthesizer swells, and because it’s a war movie with chase scenes there are rhythmic-heavy marches, and because it’s an American movie in Afghanistan (though it was filmed in Israel – I know, tisk tisk) there is wordless ‘ethnic’ singing sometimes. Yet while I mention these things, it’s also exactly what makes this film score so great. Some parts, I would even liken it to Muslimgauze, but more composed, and multi-conceptual.

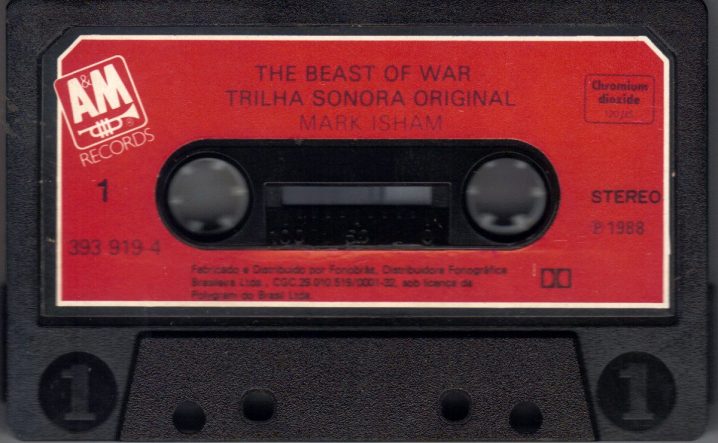

Though it is split into 10 tracks, the cassette that I have is labelled as only 2 tracks, one on each side, which adds to the intrigue. It’s easy to get lost in it. When a musician makes set tracks and then purposefully throws it off, it becomes an even different being. Like any great score, there is a theme, and it recurs. After more than 25 years what it retains the most is the time, and the mood. Some people like it always changing, as if the composer is too lazy using similar parts throughout. But that’s what I’ve always liked about film scores. Here, you just get lost, and it feels great.

Words by Will Long // twoacorns.jp and celer.jp