Interview by Joachim Spieth. Photo by Christian Kopp.

Republished on Headphone Commute with permission from the author.

The Berlin-based musician and label owner Głós has created his own Non-Print label in recent years, whose music builds bridges between bed and club. Since I have been dealing with this approach for a long time, it was interesting to exchange ideas personally.

— Joachim Spieth

Can you tell us a little about how your project came about? How and when did “everything” start? When did your love for the production of Ambient music emerge?

Truth be told, I might have loved Ambient music already before I even knew it was an actual genre. Looking back at things, I must have been 16 years old when I got my first Electric guitar, coming with an amplifier and a multi-effect pedal. I was into Shoegaze at the time, Loveless by My Bloody Valentine was basically my religion, and I used to lock myself up in my room, plug headphones into the amplifier and just create blurry walls of sound, totally getting lost in them. It was highly meditative and I remember I always wished people could enjoy this kind of thing, but I wouldn’t know better. It wasn’t until my early 20s that I discovered the existence of the genre through a friend, introducing it to me with the words “Ambient music is the kind of music that heals the pain inflicted by other kinds of music”. Before that, I was listening to video game music a lot when I was a kid, or film soundtracks. I mean, obviously, I still do. That was, however, until I discovered Rock music, and even then, I always tended to like the interludes and album skits almost more than the actual hits and singles. That friend I mentioned, he showed me music from The Leaf Label, like Colleen, he showed me Tim Hecker, Jan Jelinek, introduced me to the Kompakt Pop Ambient series. Before that, I thought ‘Treefingers’ on Radiohead’s Kid A was an extraordinary thing to put on an album. I loved discovering this kind of music so much, it sort of felt like having an actual soundtrack to my own life that wasn’t tied to a specific video game or film. And the 16-year-old inside me was so pleased with that there was a scene for the music he initially made with his guitar in his bedroom.

Głós then came about only a bit later, when I finally decided to actually indulge in a solo music project. Although I already was into partying and, subsequently, Electronic music at the time, I kind of struggled with making the step to make such music myself for the sole reason that seemingly everybody suddenly became a DJ overnight. That was around 2008 when all the people surrounding me started to shift their musical interest from Rock and Indie towards Electronic music—either because of partying or because of the Electroclash hype of that period. Literally, everyone swapped their guitars for CDJs that year. I remained in a band and was stubbornly active as a VJ instead for a while, struggling with the usual problems that would accompany me for a lifetime: my ambitions and musical ideas were too extraordinary for the band I was in at the time, and VJing was a bit unfulfilling because nobody cared for visuals in Dortmund. Then, all of a sudden, Dubstep and Berghain became a thing on the internet—and I say internet deliberately as either of those two things might have been a thing in cities like London and Berlin, but surely not in Dortmund where I was living. Still, discovering this deep and atmospheric type of dance music pushed me over the edge. After listening to Appleblim’s Resident Advisor Mix and discovering Scuba’s A Mutual Antipathy, Shed’s Shedding The Past and Sten’s The Essence pretty much simultaneously, I gave in and started my first attempts at creating music at home on the computer. It just put the right images into my head and this would also be the first time for me I could actually create a final musical product in the form of a song without relying on anyone else and without having someone talking into my creative process and making me compromise the ideas that I had.

My first release came about in 2013 after meeting Ekserd—also over the internet—and perhaps a bit too early in hindsight. I was living in Cologne at the time and had a very clear vision of where I wanted to go musically, but I still lacked the skills of getting there. Only as of 2016, having moved to Berlin already and after my first little underground hit entitled Cut Throats, I felt that I have really found my voice. With Filling The Scars With Light, I also brought out my first Ambient release that year, an EP inspired by the work of William Basinski and Angelo Badalamenti. For most of my musical career, I have been a Techno artist first and an Ambient artist second. But as time goes by, Techno becomes more and more difficult to enjoy for me. The scene has made a huge shift towards “harder, faster, stronger” and it becomes more and more impossible to get people interested in music with content that isn’t about raving your tits off. And don’t get me wrong, I do like raving my tits off once in a while, but there is more to music than that. If you’re an artist and you’re basically stuck to only being able to do one thing and nothing else, it becomes enormously frustrating. It’s like being a painter and being forced to only use the color red for a lifetime. Ambient became more and more fulfilling because of that. There is no expectations. Nobody expects an Ambient track to be a hit, nobody expects it to make money and to fill a club. It’s also not about being an influencer on Instagram as much as with Techno, and surely not about posting the right selfies either. It leaves actual room for being artistic and for expressing one’s feelings. When Techno is the music that goes with being out, pumping your fists in the air and being surrounded by people, then Ambient is the music that goes with being in bed with the person you love, doing the things you love. In the end, it’s all about the mood and the right soundtrack.

You have just released a new album, entitled When Things Cast No Shadow. How would you describe the musical development compared with others? I can tell that the pieces are a lot shorter on average than on the previous albums. Was that more of a coincidence, or was it consciously?

I think the core difference is that while I had a very clear vision and a concept in mind that I wanted to achieve with Music For Sleepovers and Music For The Morning After, the music for When Things Cast No Shadow I sort of just created piece by piece, without actually having an overarching idea of what it might become at some point. Sometimes, when you indulge in a musical project and got it out, all you want to do is to turn around and make the complete opposite. I did so in creating a Techno album—Wounds—that got released on Diffuse Reality earlier in November. Before that, though, the first lockdown hit Berlin in March 2020 and I just so happened to be in the mood to make music almost every day as I had very little to no distraction in doing so. I made one track after another, some Techno, some Ambient, as per usual. And even while I was working on Wounds, my attention also swayed towards making Ambient sometimes. Suddenly, I had a significant amount of finished Ambient pieces that I probably couldn’t sign anywhere, so I decided: Let’s make it another album. Because why the fuck not.

The pieces on When Things Cast No Shadow are indeed mostly shorter, and I feel that the album is more diverse due to the lack of an initial overarching theme. The theme of the previous two albums was the loss of who I thought was the love of my life, an event that made me lose the ground below my feet. I struggled with this enormously, to a more than a worrying degree, and creating those albums helped me out of it. This is why the music on that albums turned out extremely long and painful overall—because it came from a dark place. If I would now have to name an overarching theme for When Things Cast No Shadow, it would be finding peace. Sure, a lot of the pieces still sound dark or gloomy, but in the end, they’re neither hopeless nor about pain. They’re about acceptance, about finding your place in the world. About moving towards the light. There is also some sort of cyberpunk imagery going on, one can hear the humming of spaceship engines and consoles bleeping, which isn’t all that typical for me. But I guess, in a way, it’s about moving towards the sun and away from what’s keeping you down.

You have been playing live for some time, how is your set structured, what are the main differences between the setup and the way you work in the studio?

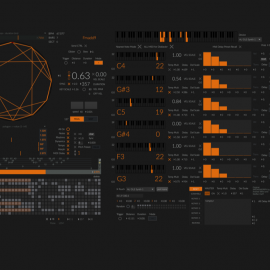

There is a fundamental difference for me between playing live and working in the studio, or rather a bedroom, in my case. In the studio slash bedroom, I don’t care about functionality or how to reproduce any of the music I make, I just create whatever occurs to me or what I’m in the mood for. Anything goes, really. I would sample a saxophone for a break within a track and not think about whether I would bring a saxophonist on stage—which of course I wouldn’t anyway—or just play the same sample via a launch pad. In a live environment, on the other hand, efficiency is key. I made some unpleasant experiences with suddenly unfunctional hardware in clubs and decided to go with a setup in which as little as possible can go wrong. It’s been a gradual way of stripping down all the tools to the most acceptable minimum to ensure I can still pull off playing with people dancing in the booth and pouring beer over my back. Please don’t do that, by the way. For the last years, I therefore never travelled with anything else than a laptop and two small AKAI controllers, not only because I wanted to carry as little as possible, but also because a lot of clubs only offer limited space for live setups in their DJ booths. I had to grow accustomed to the fact that I needed to put controllers on one record player and the laptop on a tiny square of free space where people usually put their drinks.

It similarly works with the content being played live. My pieces are very complex and although I tried it in the beginning, it’s next to impossible to actually play every little aspect of them live. I would need one or two additional people to play every element of every track. So now, I either play the melodies or the drums. However, I feel like, for the future, I might in fact try making more stripped-down music that can be played in a live context entirely without any cop-outs. On a side note, I often come across people with incredible expectations towards live acts. I had dudes standing in front of me telling me I wasn’t a real live act because I only play drum parts while I loop melodies, or vice versa. They expect you to have fifteen arms and sixteen legs to play keys and turn knobs, preferably also ten dicks on top to push your pads with. Sole live acts who can pull that off are great and deserve deep respect, but one should keep in mind that the music is structured accordingly for such settings. For me, the music comes first, and then comes the thought of how to perform it live. In the end, I feel like I owe the audience that everything goes without hiccups and interruptions, to avoid breaking their immersion. I want people to have fun and to be in the moment, and not think about me standing there and playing for them. Contrary to what some people might mistakenly think, playing Techno in a club is unlike playing a concert. People only care for you standing in the DJ booth when you’re super-famous, but when you’re me, nobody gives a fuck, people just want to dance.

Which main components (software / hardware) characterize your work? Are there any tools or certain procedures that have become established with you?

Definitely Ableton Live. I do everything in Live for at least 10 years now, for efficiency reasons. When I’ve got an idea for a piece, I want it finished in one go, preferably within a few hours. My work is heavily based on samples as I spend a lot of time on the internet, absorbing different forms of media. Sometimes I watch a film and there is this one phrase that inspires me, sometimes I see a weird YouTube video with weird sounds in it. It could basically be anything and I rely on that far more than on specific instruments, plug-ins or hardware.

I’m glad you’re using the word “tool”, by the way, because there are recurring habits or mannerisms that repeat throughout my catalogue. The most obvious ones are heavy use of reverb and sidechain compression, other habits are the use of field recordings such as rain or the sound of passing cars in empty streets. All these are tools to me that help keep my work together. Regardless of how different my style will be in the future, there will always be those things that will keep it “glossy”. I think it’s safe to say that the leitmotif within my work shall forever and always remain intimacy. At least as of now, I can’t think of anything that would have greater value for me than the moments you share with people, the encounters you make, and the relationships you have. And even should it be the lack of intimacy, like when partying and being in crowds, it’s only a part of the bigger picture for me. Which is why I don’t distinguish so much between Techno and Ambient. For me, it’s the same: a soundtrack to special moments.

Some time ago you founded your own label, Non-Print. Is there an overarching concern or concept that you are pursuing with it?

The overarching concern and the concept of Non-Print are best explained by the long history of personal failure that lead to its creation. You see, I’ve had the idea of starting my own label for at least as long as I’m active as Głós. And I can’t tell you how many times I was on the verge of making it happen, with releases planned out, the music already being mastered, the artwork ready and done—and then, it wouldn’t happen, because of either financial struggle or other higher forces. Honestly, it’s as if I were cursed, there was just always some sort of little catastrophe around the corner dooming every attempt of putting the first 12″ out to failure.

It was in 2018, when I came to the realisation that if I’d want to start a label it would have to be digital only or it was probably never going to happen. That thought depressed me a lot and I struggled with it initially—because especially in the Techno scene, there is this mindset that a digital release will always be inferior to a physical release. I mean, you know how it is, the vinyl industry may be struggling, but in Techno, you basically still need to put your music out on vinyl for people to consider it worthwhile listening to. This perception might probably be more and more shifting with newer generations of listeners, but for as long as I can think, this has certainly somehow been the case. Then it occurred to me: what if I just let go of that whole inferiority concept and flipped the table entirely? What if my label would instead celebrate the fact that it was digital and find a way to make it look like it’s not a compromise at all? What type of content could I produce that would in fact be inferior in physical form? It was almost like having an epiphany because 2018 was also the year in which my debut EP on Ressort Imprint would celebrate its fifth anniversary—and as I mentioned earlier, I wasn’t necessarily very happy with how it turned out in hindsight.

I came up with the idea of reworking my older music that I thought wasn’t realised ideally. And it wouldn’t take long until all the re-working, re-writing and re-making would turn into something that would exceed the average album length. And while working on it, I realised how many limitations I would face if I were to optimise this album for physical formats. I would always come to a point where I needed to cut content or adjust the music to make it fit to a specific medium. I decided to entirely ignore any of it and make an album that would exist completely outside of those boundaries. That way, I wouldn’t have to think in four or six 15-minute blocks for the sake of making it fit on three 12-inches or anything like that. I could allow for tracks to be overlength, structure them how it felt natural and make the tracks grow and expand, letting them breathe freely.

And before I knew it, I found a sort of freedom for myself that I didn’t even know I was lacking. With easier ways of digital distribution, I could even make it come out on the exact same date as my EP just by uploading it to Bandcamp. I tried to expand on this idea with Twenty-Three Stabs, a single that was exactly 23-minutes long and that would be non-sensical on a CD, vinyl record or cassette release. And I took it even further with Music For Sleepovers and Music For The Morning After, albums that exceeded the 80-minute mark by far and that would have pieces on them that were almost an hour long. I could literally go bloody bonkers with this, and I liked it. This concept made me challenge my own understanding of what music could be, and I found it incredibly satisfying. Finally, the name ‘Non-Print’ derives from the idea that there is no need to print any paper sleeves or CD inlays because they wouldn’t exist in a purely digital world. It’s become about turning limitation into a place of non-compromise, and I began to fully embrace everything that had to do with it. It’s a place for all my ideas that wouldn’t find love on any other label, almost like a dog shelter. Whenever any label would say No to my music, Non-Print is the place I could say Yes. I’m still looking into new places I could go with it, and I’m also already working on a line-up of upcoming releases—trying to find new boundaries that I could push for myself.