The following is only an excerpt from an Interview with Abul Mogard, who is currently the featured artist on Headphone Community. For just $1 a month, you can join us in this intimate discussion, where you’ll also have the opportunity to ask your questions. Inside, you will also find previously unreleased tracks, massive discount codes (75% OFF albums!), and many other exclusive perks! Plus, you get to hang out with Abul Mogard! The real game-changer of this new platform lies in the fact that every monetary contribution goes directly back to support the artist! Join us now for an ongoing conversation about music, where this interview is currently in progress, published in multiple parts!

How would you describe the sonic aesthetic you’ve cultivated as Abul Mogard? What elements or qualities do you consider most essential to your sound?

It’s hard to describe your own sound. I generally make music that evolves slowly, often without a defined tempo, and is often hypnotic. It began with minimal pieces made from just a few elements, but over time, it became more layered and complex. I like simple melodies and try to give each piece a distinct sonic signature, something recognisable from the start.

Over the years, your sound has evolved into a more complex and layered one. What drove the evolution of your production approach? Were there any turning points or new techniques that significantly expanded your sound palette?

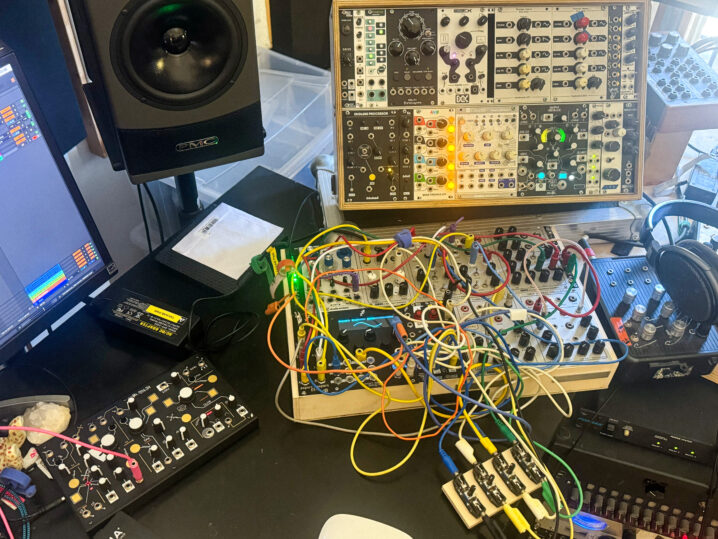

It mostly depends on my experience and my curiosity to explore new sounds. When I started the project, I didn’t have the equipment I have now. The first album, the self-titled one released on cassette, was the result of me trying to work alone after many years of relying on collaborations. I had lost confidence in my ability to finish music by myself, so I began recycling unused sketches from other projects and using them in new ways. For example, I would take a small section or loop and process it through a pre-amplifier I had built, a Neve 1073 clone, and then through some home-made filters I had recently made, just to see how far I could push the sound. I continued using similar methods later, but started creating new compositions specifically for this project and bringing in more instruments. Later, I acquired a Moog Voyager, which became a major part of the sound on Driften Heaven, the second cassette release. Again, I kept pushing that sound to see where it could go. Then I built a modular synth combining so-called West Coast and East Coast modules, honestly without knowing they were considered such different approaches to synthesis. I used that synth extensively on Circular Forms, which really shaped the album’s sound. With each release, I kept exploring new directions and possibilities. In general, I see it as trying to make things more extreme each time in one way or another, whether that means exploring longer-form compositions, using more sounds, adding more distortion, or introducing more complex harmonic structures.

Many of your pieces feature dense layers of sound where subtle details reveal themselves over time. Can you share how you approach sound design and layering? Do you start with a particular texture or drone and build around it, or experiment with various sounds? Any specific techniques you use to keep long-form drones engaging and dynamic?

I am very interested in flow. For me, it’s really important that a piece carries you from start to end, with new details coming in throughout. A lot of the time, I start from an improvised recording. It could be when I find a sound I really like on a synthesiser, a loop that feels engaging, something on the modular synth that suddenly becomes interesting, or a chord progression I connect with and need to record right away. I record it and then try to understand whether a specific section is all that’s needed, or if a longer one works better. From there, I usually add something on top, trying to fill the gaps. It could be a new melody that enriches the first one I recorded, or sounds that give the composition more depth. I spend a lot of time mixing the sounds. In fact, mixing is part of the composition process for me. I don’t really have a separate mixing session at the end; I just keep building, changing, and removing until it feels right, and I find that depth and flow I’m looking for. So recording a good take, something that speaks to me, is very important. Then I might shape the dynamics using effects like delay, reverb, distortion, filtering, and very importantly, automation to keep the sound moving.

There’s a fascinating tension in some of your music where harmonious calm intersects with dissonant, uneasy tones. You’ve mentioned being inspired by Phill Niblock’s idea of pushing sound to the edge of discomfort. How do you incorporate slight dissonance or “friction” in your compositions while still maintaining the beauty and meditative quality?

Yes, listening to Phill Niblock made me think more about dissonance and how to explore it. For me, it’s about finding a balance between consonance and dissonance. I often try to push the music to the point where it almost dissolves or becomes imperceptible, but I stay just on the edge of that. On this album, I worked with similar sounds and melodies that drift slightly apart. That’s where the tension comes in. Sometimes I layered elements that are almost the same, just different enough to clash gently. I was drawn to that friction and tried to take it as far as I could while still keeping a sound that felt like mine.

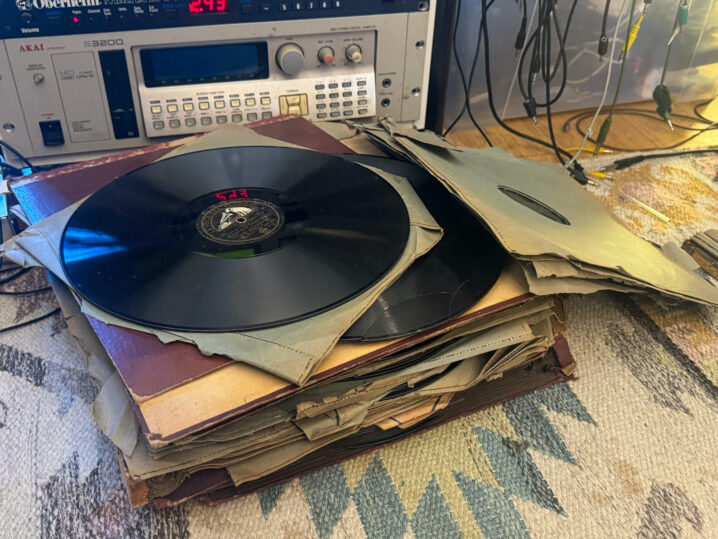

On your latest album, Quiet Pieces, you integrated fragments from 78 rpm records of classical music that once belonged to your uncle. What inspired you to blend these archival recordings into your music? How do these decades-old sounds interact with your modern synth layers in terms of atmosphere and meaning?

It was a chance discovery in the attic a few years ago, when I moved back to Rome after several years in London. While clearing the place and sorting through things, I found this box of 78 rpm records. At first, I planned to make a separate album using samples from these records. But as I revisited some older pieces I wanted to release, I began merging the two to see what would happen. I integrated the samples into older tracks and also worked on new compositions built around them as a core inspiration. What I like about this approach is that, since I didn’t make those original recordings, they interact with my ideas in unpredictable ways. It feels like a conversation with a distant voice from long ago.

Your compositions often stretch out and alter the listener’s sense of time – minutes can feel suspended or “elastic” inside your music. What does “time” mean to you when you’re composing? Do you intentionally play with the perception of time passing (for example, through gradual transformations and sustained tones) to create a meditative state?

I think I play with time so that the perceived length may differ from the actual length. It’s not something I do intentionally but something that comes naturally to me. Sometimes, in conversations like this, I realise things I had not thought of before, like now, for example. It’s interesting because recently I was asked a similar question about time by another journalist, and that was the first moment I truly reflected on it. In general, when I work on music, I try to keep things natural, so the length of a piece is whatever feels right at that moment, whether during recording or while editing and arranging.

Ambient pieces can theoretically go on indefinitely. How do you know when a piece you’re working on is finished? Is there a particular feeling or moment of clarity you get when the music has reached its ideal form, or do you decide practically that it’s time to stop adding layers?

A piece is finished when I feel the depth I’m searching for, and that depth brings a certain emotional response, whether calm, tension, or something else unique to the piece. As I mentioned earlier, I don’t want to force a specific emotion; what I describe here is my personal response. Equally important is that the music holds my attention from start to finish. That sense of connection lets me know the piece has reached its ideal form.

Continue reading on Headphone Community…

…where you can even hear what that Farfisa organ sounds like!