Hi Daniel and Gareth. Where are you these days, and how are you holding up?

GARETH: I’m doing very well, thank you. I’ve had a creatively productive lockdown. I had COVID, but I didn’t go to the hospital. I’ve had my double vaccines. So I’m feeling blessed I’m still alive. Right now, I’m in my little studio in Shoreditch, where I’ve been on and off for very many years, and it’s great to chat with you guys.

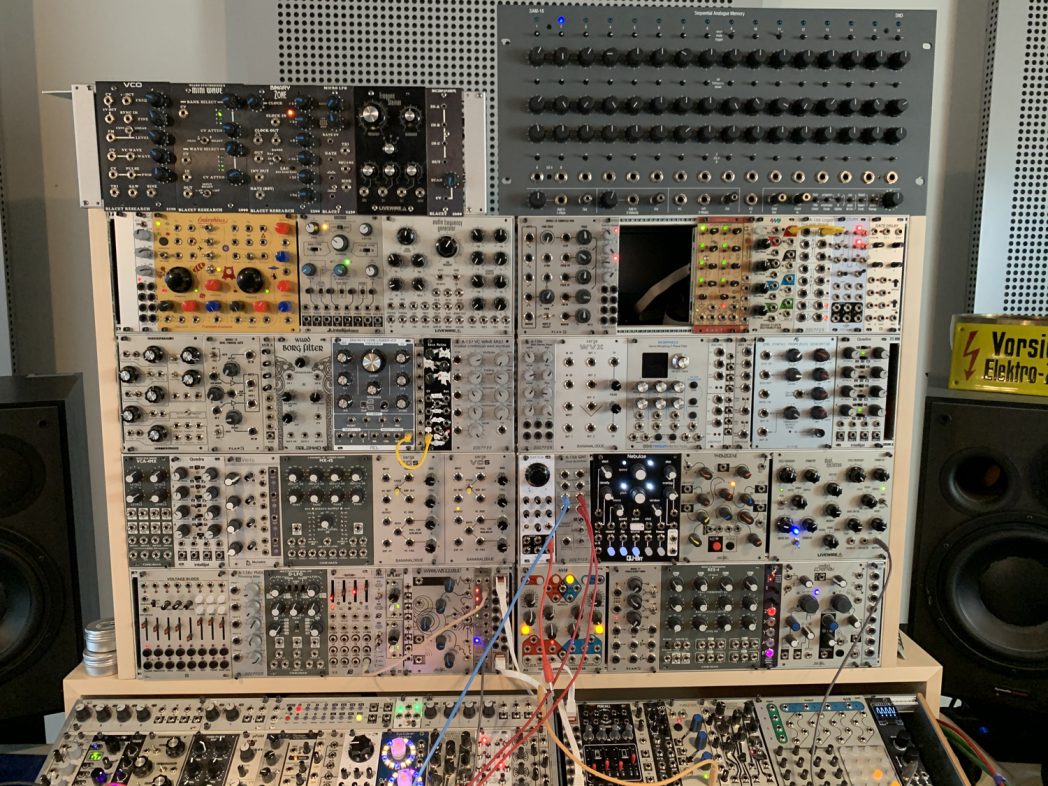

DANIEL: I’m doing fine apart from my vaccine hangover. I’m in Berlin. I’ve been here since March 2020, apart from a couple of little trips into the rest of Europe. Before that, I used to commute to London. Both Berlin and London are my home, but this is where my wife is. It’s been great, apart from lockdown. But it’s great being in Berlin. I’m sitting in, well, it’s not exactly my studio, it’s where my modular is. I’ve been doing a lot more in here since lockdown. It’s given me more time. No travelling. I used to travel a lot. So I’ve got loads of time to play around, which has been fun.

Tell us about the recently revived Parallel Series.

DANIEL: The Parallel Series kind of went into hibernation in 2003. It’s a bit of a story because it also goes back to our thoughts about this record and how we wanted to release it. When we started this project, we had no plan to release it. We didn’t know if we would like it, if it would be any good, if the process would work. So we didn’t start the project with the aim of releasing the music. It was in the back of our minds, I guess, that if we liked it, then we would release it. We would somehow get it out there via SoundCloud or Bandcamp, kind of a quiet way out.

I mentioned to Joff Gladwell, Neil Blanket, and Paul A Taylor at Mute that Gareth and I had done this music together, we quite like it, and we might put it out. “I just want to let you know we might release it on SoundCloud or Bandcamp.” “No!” they said, “it’s got to be on Mute.” I said, “OK, but it shouldn’t be on Mute the label, why don’t we put it on The Parallel Series?” And that’s really how The Parallel Series came back.

If and when we do more music, I’m sure that it will come out via The Parallel Series if it’s approved by the record company. I haven’t really conceptualized the label. It wasn’t a modular label before. It was kind of a label for music made using experimental processes. But I thought maybe we should just make it a modular label. I haven’t figured it out yet, but that could well be the plan.

GARETH: That’s a good summary, Daniel. Obviously, as a long-term friend of Mute, I’m delighted that we are releasing the record on Mute. I never expected to, to be honest. In my memory of it, I was pushing to get some advice from Joff and Paul about if they knew a good home for the work we had done. I was excited to play it for my friends at Mute, and I wanted to get some advice on where we might punt it, where we might get a little label to put it out. Obviously, a label is a wonderful thing because it means we have to do less ourselves. So that’s how it went for me. Then, when Daniel told me that Joff, Paul, and Neil had basically put their foot down and said they’d love to put it out on Mute and that it should be on Mute, I was obviously delighted for their support.

DANIEL: Yeah, I remember that extra bit about getting advice. I think we said to Joff – because he’s very knowledgeable about smaller, independent kinds of labels – “any thoughts where we could release it?” And he said, “yeah, Mute.”

What was that one moment where you thought, ‘okay, time to finally make that studio album as Sunroof”?

DANIEL: That wasn’t the decision. The decision wasn’t to make an album. We’ve done jams over the years, and they’ve been quite long and meandering and not really finished in any way. I think it was more like, let’s make some music and finish it. That was the first goal.

GARETH: And also, oddly enough, it was never planned as a Sunroof release. It was only when we got to the end that we needed a project name. And then we realized we had one already, so we might as well build on our brand.

Can you describe some of the modular gear used in the sessions?

DANIEL: The first thing that’s important to know is that we used our travelling setups, not our studio setups. So they’re very flexible, but a bit smaller than we have in our studios. From a sequencing point of view, the heart of it is a Five12 Vector Sequencer. I think it’s absolutely brilliant and does tons of stuff that you don’t immediately realize until you start playing with it. Other key modules would be something like the Klavis Twin Waves oscillator, which is two oscillators, actually.

Of course, when you’re working with a relatively small format, like a travelling case, most of the modules are pretty small. The biggest module, apart from the sequencer and the mixer, which are in a separate little rack, I’ve got a Befaco mixer, a Hexmix. For live, especially, it’s a godsend to have a really good mix with that. The Malekko Voltage Block is really important. That’s the biggest module in the main case. That’s an 8-track modulation sequencer. I really like the Euclidean Circles from vpme, which is a way of creating euclidean rhythms. Also, The Noise Engineering BIA is kind of a percussion synthesizer.

Obviously, the ones that are super important to me are the ones I collaborated with Future Sound Systems on. Those were inspired by live use. I wanted to be able to make big changes in sound. Once you’ve got everything plugged in, the case gets really crowded with cables. You’ve only got two hands. So you can only change two things at once. But I wanted to change a lot more than that and create quite different sounds and textures. Future Sound Systems is a modular synth company that also collaborated with Chris Carter as well on The Gristleizer modules, which is how I met them, actually.

There are two modules we did. One is called Macro, which basically is one main knob with six voltage outputs. Each output has an attenuverter on it. So you can control the level and polarity of each output. And the main knob is how you change all of those outputs at once. With those six outputs, for instance, I could control the filter frequency, I could control wet/dry with an effect or delay, I could modulate an LFO, I could modulate a VCA maybe where that LFO goes through in order to bring it in and out. So when the knob is to the left, there’s no LFO modulation. As you go through it, it gradually gets deeper. It’s really great for live, but also for the studio as well. As I said, at any point, you’ve only got two hands. This gives you six extra hands.

And the other module that we did is called STUMM, and that’s a mute switching module. That means you can cut things in and out. There are quite a few of those modules on the market because they’re very useful. But with this one, you can group the mute. Say, classically, I have a kick drum, snare, hi-hat, and other percussion. So I have four sounds, and I just want to keep the kick drum in and cut the others out. With one switch, I can do it. Instead of having four switches, I can group them into one switch and cut them all out at the same time. Very handy.

And the case is an Intellijel 7U-104 case. It’s two rows of 3U, which is the standard Eurorack height format, and one row of 1U. And I basically just have little mixers and attenuverters across the top row, again, to help control things while I play.

GARETH: That’s Daniel’s case. My case is the same and is inspired by the Make Noise Shared System. I’m a huge fan of Make Noise Music who is a wonderful boutique manufacturer based in Asheville, North Carolina. Like Daniel, I have a 104 3U that generally has controllers in it. I found great creativity and joy in the Pressure Points, which is a big part of my control rack. I’ve got eight steps where I can send voltages or variable voltages out of the Pressure Points. For me, that was a big step forward in modulating synth patches because I can modulate them in such a way that when I let go of the Pressure Points, the sound goes back to where it was. I find that to be very gratifying if I’ve got a core sound, and then I can change it quite radically, let go, and it goes back to the core sound. This was always a problem I had before I discovered something like the Pressure Points or the Macro. If I changed my core sound, it was gone forever. So I was unable to do this kind of revisiting.

My core sequencer is a Make Noise Rene coupled with the Tempi, the clock source. Like Daniel, my rack’s changed a little bit since we did the improvisations together because that’s one of the joys of modular. You can constantly unplug devices and re-plug them to create a new instrument. Having said that, I basically put together a Make Noise Shared System, but I didn’t buy it all at once. I bought the modules as and when I could afford them. I must add, in that year when we were doing the improvisations, I was deeply in love with the Strymon Magneto echo box. That was a core part of my rack. Quite big, but worth the space because I’ve always been a fan of synced delays and reverbs. This box is really good for me. I could probably go on and on, but that’s probably enough for now.

DANIEL: Just two things to note: neither of us had a conventional, piano-style keyboard. The other thing is that we ran it in sync. We had a master clock that was sent to both systems so we were in sync with the sequencers and stuff. Which is not necessary. It’s quite good to do it without it as well, but I think we did that on quite a lot of the tracks.

GARETH: Obviously we’ve spent a lifetime together working on sync. I think we took advantage of that by just connecting. Most of the time, we recorded the outputs of the two modular cases separately. They were recorded as stereo pairs, so there was no real mixing to be done afterwards. There was one occasion, and I can’t remember which room we were in, where my rack appeared in your mixer, Daniel, and it went straight to stereo. I remember sending audio to your mixer. I don’t think we had an audio mixer with four ins on that particular day.

DANIEL: And just on a technical note, we recorded into Ableton Live as though it were a tape recorder.

GARETH: In fact, we’re talking about doing a recording project onto a four-track tape recorder. I believe your four-track tape recorder is now refurbished, Daniel, am I right?

DANIEL: My original 1/4″ TEAC 2340, which was the budget version of the 3340 back in the day. Yeah, we should use that. That should just be our Sunroof recording device.

What is the next module that you already have your eyes on?

DANIEL: The thing is, I’ve got a lot of stuff. There’s something I’m looking at now to serve a particular purpose. But I can’t remember what it’s called. It’s a very simple module for gates and triggers. Stuff like that. It’s got six inputs and you can assign each input to one of two outputs or switch it off. The particular reason I want to use it is because I’ve got a clock divider. When you put one clock in, or a trigger, you get lots of outputs. I want to be able to assign those outputs to one sound or two sounds. That’s just one thing I’ve been looking at, but there’s no rush.

GARETH: I’ve always been interested in sampling. Obviously, we were there at the beginning with samplers. I have recently put a Big Box Micro in my rack which I’m quite enjoying as a sampler. But I’m interested in exploring the Eurorack sampling field more and maybe some looping. But I have more than enough modules to keep me entertained and creative for the rest of my life as it is. I’m sure I could be learning about the modules I’ve got until the end of the century, probably.

What were some new synthesis techniques that you have recently discovered?

DANIEL: I don’t know about techniques, per se. But there are so many different ways that you can patch the system together, you’re always learning new things. When I got into Eurorack, which was a few years ago now, I started using a lot more things like wave folders and function generators. The wave folding is great, it’s like additive synthesizers. Classic Moog-style synthesis is subtractive. In other words, you’ve got a waveform like a sawtooth wave and you put it through a filter to reduce the harmonic range. That’s the kind of classic sound of most synthesizers. When using wave shapers and wave folders, you put a sine wave in, which is the most basic waveform, and you can add harmonics to it, rather than take away harmonics. It’s just a different way of making a sound.

There are two categories of modular techniques: one is East Coast which is the Moog, subtractive technique and one is West Coast which was pioneered by Don Buchla in the 1960s which is more of the additive method. It’s a bit segregationist. My system is very multicultural in that sense.

GARETH: That’s why the No Coast was invented.

DANIEL: Exactly. It’s a multicultural, multi-coast system.

GARETH: One technique that very much came to the fore when we were improvising together was deep listening and very focused listening. It’s clearly not a synthesizer technique, but I think of all the techniques we used while we were performing and writing together, it was super important.

We didn’t speak about any of the compositions before. We both showed up with blank cases, nothing plugged in, and no preconceived notion of what we were going to do. We met, had a cup of tea and a little chat, not about the music, and as we started to build sound, we didn’t talk. There’s absolutely no talking and very, very concentrated listening. Obviously, as musicians and producers, we’ve spent our lives doing concentrated listening anyway. But I feel in our sessions together on this album, we honed that skill. We were required to listen so deeply to each other and to the noise coming out of the synthesizers. Sometimes it wasn’t even clear who was making which part of the noise when it was very dense. But I can’t underline enough how important of a technique that is – listening.

DANIEL: One of the things I’ve explored more, especially over this last year, is with a vector sequencer which they’re constantly updating, the Five12 Vector. It’s got a lot of rhythmic possibilities that emerge – things going in and out of phase, for instance, externally modulating tempo with LFOs or random generators. That’s not a technique, just learning how to use the thing properly and exploring it.

Talk a bit about the improvisational aspect when creating this record.

DANIEL: Under the Sunroof name, up until this project, we’d done remixes. It was our remix name. There’s a very clear beginning, middle, and end process when doing that and a very specific purpose. We have improvised before. When we worked together with bands, when they went home or at the end of the day they might go off for a drink, which we did as well, sometimes we just stayed in the studio. Working with a band and amazing songwriters is great, but sometimes you just want to free yourself a bit from that and enter your head. One of the ways we did that was with modular jams in the studio late at night. For nothing other than having fun.

GARETH: I think this notion of pleasure is important. Because Daniel and I both have day jobs, the Sunroof improvisation project was put together in our private time. And that time is very precious and limited. We were trying to make complete pieces of music as effectively and quickly as possible. One way that seemed to work for us was improvisation. That’s not to say we used every improvisation because loads of them didn’t make the cut. I was very nervous about the rabbit hole of building a track by layers because we’d both get bored and our time would run out. The thing with improvisation is it’s either listenable or not afterwards. That was a much more binary choice instead of saying, “we might have the core of a good idea here, we might need to spend another six weeks on it.” If we had done that, we never would have crossed the finish line.

DANIEL: That’s correct. And that was the first goal – to cross the finish line.

What advice would you give to someone just starting out with modular?

DANIEL: Don’t get too many modules at once. Have a think about what you want to do with it. A lot of people use modules purely for processing other instruments. It’s a great way to do it. Do you want to make techno? Do you want to make more tonal music? And I know you kind of develop those ideas over time. You may start out wanting to do techno and you end up doing tonal, layered music.

The problem now is – and it’s a good thing and a bad thing – it’s so confusing. There’s so much choice. There’s a very useful, but dangerous website – and anyone who’s interested in getting into modular should go to – called Modular Grid. It’s got pretty much every module that’s in existence, and ones that are no longer in existence, on that site. You can design a system on there by picking the modules.

GARETH: And you can see the price at the end, right?

DANIEL: You can see the price, the size, the description, you can go to the website of the manufacturer. It’s really good. But what I’ve seen on a couple of Facebook Eurorack forums – it’s the only thing I use Facebook for, actually – you see people who have designed a system in Modular Grid, not based on using any of those things, but based on what they think might be good. It’s interesting to start smaller and when you have an idea, start basic. And when you think “I want to have more modulation or a filter or whatever,” then look for specific things. Build it up slowly and learn as you go instead of being overwhelmed by having too many modules you don’t know how to use in one go. Just learn a bit. There are tons of videos on YouTube that, again, are great, but also dangerous, because you get excited about things people are doing demos of. Start simple.

GARETH: That’s such valuable advice. It’s important to say this is Daniel’s and my second dipping into modular. This is a Eurorack modular time. In the ’80s, we both had modulars that were not Eurorack that were way more expensive and way bigger. This is the same advice that Daniel gave me when I started to dip my toe into Eurorack. Even then, which is nearly 10 years ago, it was super confusing. I went to SchneidersLaden in Berlin about three times with a budget. I basically had the cash in my back pocket, symbolically. And I did not know what to buy. I was very confused.

I’ve passed this advice on to others. Buy a small-ish empty rack and put two or three modules into it. My journey into Eurorack started with external processing. A lot of my day job is mixing other people’s records and doing record production for other people. So I felt if I was using these processing modules that allowed me to process their music, I could kind of justify the expense a bit more. That was a comfortable way into it for me. So I completely agree with this advice, but there’s another angle as well.

It’s really great to have an instrument that you can really play immediately. We’ve both recently fallen in love with the Pittsburgh Voltage Lab which is a very powerful, small modular instrument that is kind of a complete system in itself. And that is also very gratifying if you’re just coming into modular – to have something that you can kind of process sounds with, you can do weird modulations, you can play lead lines and bass lines, you can make percussion sounds. That’s also very gratifying to someone coming to modular. They’ve got an instrument that they can actually play. My friends at Make Noise have tried to address this with the Strega and the 0-Coast. These are semi-modular instruments that you can get going straight away. There’s a huge benefit in that. You have to be very hardcore to sit with your empty rack with one oscillator in it and say, “here we go!”

DANIEL: For people who aren’t very experienced with synths, the semi-modular route, to start with, is quite good. That was my first modular back in the day, an ARP 2600. You don’t have to actually patch anything. Everything is connected internally, but you can override those internal patches. There’s lots and lots of good semi-modular. The Moog Mother is a classic one. There’s a Pittsburgh-made one. The Voltage Lab is fully modular, but there are some quite reasonably priced ones just to get you going. And you get sounds immediately because things are patched internally but then you can override those sounds by patching yourself. That’s another way in.

GARETH: But also, you’ve got a set of components to sculpt a sound. Yes, they’re patched as well, that’s handy. But more importantly, you’ve got the LFO, the filter, the VCA, the LPG, or whatever it is you need to get going.

A good friend and colleague of ours, Ian Dunkin, has a rule. I don’t know if he’s still living by it. He has a rack that’s obviously full by now because he’s been into Eurorack modular for many years, but if he wants a new module, he has to sell one that’s in the rack. And that can help pay the bills and stay alive because you don’t constantly expand. It can become a very addictive process when shopping for modules.

DANIEL: They don’t call it “Eurocrack” for nothing. Even if you don’t sell them, you have more modules than fit in your case so you put together a combination for a specific idea you have. I’ve got modules in drawers and sometimes I just take one out and put another one in. And if you don’t have the space and you don’t have to keep buying new racks – the racks are expensive. That’s the galling thing. You might get a 6HP84, a classic starter rack, and the rack will cost more than a couple of modules.

GARETH: That was my starter rack, the 6HP84.

DANIEL: And that’s just the box. It doesn’t even make a sound or modulate anything. When you run out of space in your first rack, it doesn’t mean you have to get a bigger rack. You just swap them around depending on your vibe at that moment.