Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

I had a 4-track studio cassette machine. Then I was playing guitar in a band and we were recording demos. After that, I had a reel-to-reel 1/4 inch 8-track. Then I had an Akai MG14D 12-track analog machine which is really weird. It was on like videotape, but not really. It was a 1-inch tape. It was a special format for this machine. It was really good-sounding. Not really reliable, though. I remember starting my first album with this machine and really enjoying it. In the middle of the recording, I bought a 16-track and it was digital and I thought “that sounds awful.”

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

In the Eskal, there are three studios. There is studio A, the main live room, which is quite big and also a 200-capacity venue. And with it, there is the control room with an SSL 66-channel G-Series. Then there is studio B which is more focused on electronic music with my collection of synths, my modular synths and an API 24-track 2448 desk and a tree audio valve desk. It’s an American studio. The two desks are from the US. And then I have an MCI 16-track. I have a third studio that is more of a writing studio. Or when the other studios are busy I’ll do some editing and mixing.

Tell us about your favorite piece of hardware.

I have two esoteric audio research compressors. They are my favorite. They’re so beautiful, it’s crazy. Another thing that is far less expensive, that I really love especially for strings, is the Electra Kush Audio EQ. They’re not that expensive and they’re really, really good. They sound amazing. I’ve never found something that good for strings.

And what about the software that you use for production?

I try not to use too much Ableton Live because I love it and tend to use it a lot. Everybody is using it because it’s so good. It’s not really original but I love it.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on and do you think one day you’ll have it?

I’d love to get my hands on an ARP 2500.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your new album?

For Portrait, it was a first for me to go full analog. There are a few exceptions on vocals because Blonde Redhead were unable to make it to the studio. So I thought, “OK, it’s stupid to say ‘no’ because you want to stick to the analog rule”. So they sent files and it’s great. But we stuck to analog for the rest. And that was really, really good for the process. I rediscovered analog and I love that. I don’t really want to go back to digital. You have to choose at every step. It can be painful sometimes. It’s not always practical, but it’s not about being practical.

That’s the problem nowadays. We have millions of new and practical tools that save us from doing the hard work. But actually, creation and inspiration are in the hard work that we try so hard to avoid. Going through analog is helpful for creativity to be involved in every step of the recording and to commit. Like everybody, I use digital and I work with my laptop. But what I don’t like with digital is you can always go back. And that’s artificial. You can’t go back in real life.

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

For the All tour, there were four of us on stage. We had acoustic instruments, shamanic drums, tubular bells, piano, violin. There was a mellotron. Not a real one, but a new digital one. I also had my Moog and a modular setup to treat the live sound in real-time and add texture and electronic modifications. We also had an MPC with a few samples that were treated. For the EUSA album, there were field recordings on all of the tracks. For that tour, we had a Revox 2-track reel-to-reel and I’d press that the beginning and it would stop at the end.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace?

Ushant island is in the South part of the Celtic Sea. It’s the border between the Atlantic and the English Channel. It’s really rough and really stormy. When you go outside the studio, it’s really windy and dramatic. But inside, there are windows, but not much. There is a big window over the steeple. When you’re in the live room, you can think you’re in Berlin or you don’t know where you are. I love this contrast. It’s what I wanted to achieve with this studio. It’s on a beautiful island with a dramatic landscape. But when you’re in the studio, you can completely forget about it. It creates a great dynamic.

I could have gone for really big windows, playing music in front of the sea. There are big windows in the mix room. But the synth studio and the live room, it’s kind of a cocoon. You can forget where you are and I love that.

What would be a particular element that you would improve on?

The three studios are completely different in terms of sound and direction. I want to improve the interconnection between them. I have a 16-track in the synth studio and a 24-track in studio A. Of course, I can cross-patch them. There is studio C as well which can be convenient for drums or electric guitars because its a smaller space, so it’s a more dense-sounding room instead of the live room which has beautiful reverb. I have an interconnection between the studios already, but I can still improve that.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

I’m quite simple and instinctive. I play things on the piano and most of the time I just record and do overdubs to find structure. Sometimes I mess with Ableton Live. The recording process is always in the center of it. Even for my first album, I’ve always been recording what I was doing. I can’t write. I’m not a composer. I’m more into action.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

Sometimes at the beginning of an album, I spend one or two weeks saying “I will start now.” Now that I have the studio, it’s completely different. I used to live in my studio. I used to have one at home instead of having a proper studio. Maybe because of that I was spending lots of time before actually starting to work. Now that I have The Eskal, it’s completely different. I cannot go there every day to try stuff. So I’m not really a procrastinator.

I can do that for other stuff. I’m really with playlists. I put so much pressure on myself and I want to do it too well that it takes me ages to do that. I have two playlists to do and one mix. I’ve had these on my list for a month and every day I think “I have to do that” and I want to do it, but that’s proper procrastination.

What gets you inspired?

Sounds. I like to be submerged in sounds and the inspiration comes from that. It’s maybe because I started with samplers and stuff. I always see instruments as sounds instead of instruments.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

My friend from Berlin just brought me this recording and it’s really good. It’s called Anadol. She’s a Turkish woman living in Berlin making electronic music. I’ve also been listening to Substrata by Biosphere, which is kind of an old album. But I’ve been listening to that a lot.

World-renowned musician and composer Yann Tiersen is to play two very special concerts at Sea Change 2020 at Dartington’s stunning Great Hall. This will be a rare opportunity to see the pianist perform in such an intimate space when he takes over the ancient building’s hall, performing on their Steinway Grand Piano. Tiersen has long found the Schumacher College, based in Dartington, an inspiration, and field recordings from the grounds feature on 2019’s album ALL. Mute labelmate Simon Fisher Turner, who recently announced a collaborative LP A Quiet Corner In Time with ceramicist and author Edmund de Waal – out in March, will also be playing live as part of the session and a series of talks will accompany the event.

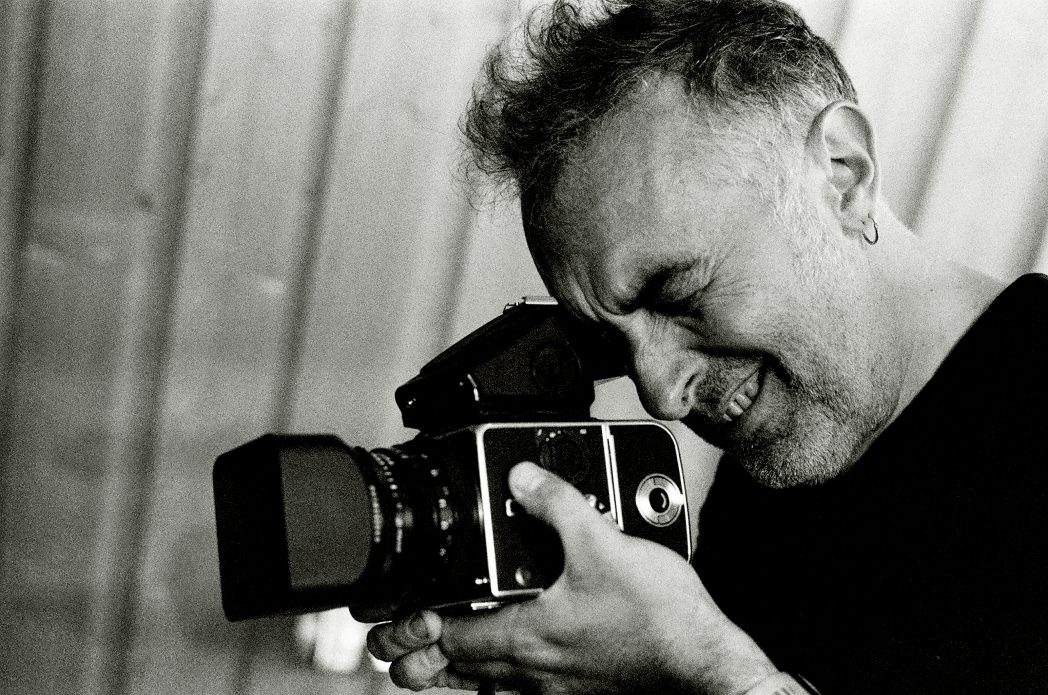

Photography by Daniel Miller, courtesy of Mute