Let’s start at the very beginning. Can you tell us how you got involved in composing, and what was your very first piece of gear?

I discovered the ‘Oxygene’ album by Jean Michel Jarre when I was a kid and that blew my mind. It was so different from all other music I heard before. Years later I was finally able to buy a used Roland Juno-6 and started playing in a band. But that was not really my thing, I always wanted to make pure instrumental electronic music. After moving to Berlin in 1990, everything came together, techno, academic computer music, computer science, and earning some money to buy equipment. I never had any formal musical education, but I read a lot and tried to learn by doing, and I like the fact that computers allowed me to bypass virtuosity in some ways. I could code an idea and was not forced to play it by hand. My Juno got stolen a few years ago, and I really miss it. It was modified to do some special things and it was used on all early Monolake releases.

How many different studio iterations have you gone through, and what does your final setup look like right now?

The first releases both as Robert Henke and as Monolake together with Gerhard Behles were produced in my small flat in former East Berlin. I had one big room which was a studio, living room, kitchen, and bedroom all at once, separated by a lot of plants. Then I moved to an empty office building right at Alexander Platz, together with a lot of other artists. It happened that Andreas Schneider became my neighbor next room, with the first incarnation of his modular synths shop, Schneidersladen. My studio was on the 9th floor with a view over the whole city and I loved that place. At some point, we all had to move out and found a new home in the former print shop of a newspaper. I got a total crisis there, I did not like the atmosphere, and one day I took it all apart and left. I set everything up again in my flat until I moved out to a larger place. Then I had a phase where I wanted to do it all in software. That did not last long, and I built a very small studio again. Recently I changed it completely as far as the layout is concerned, but my choice of equipment became more constant over the years.

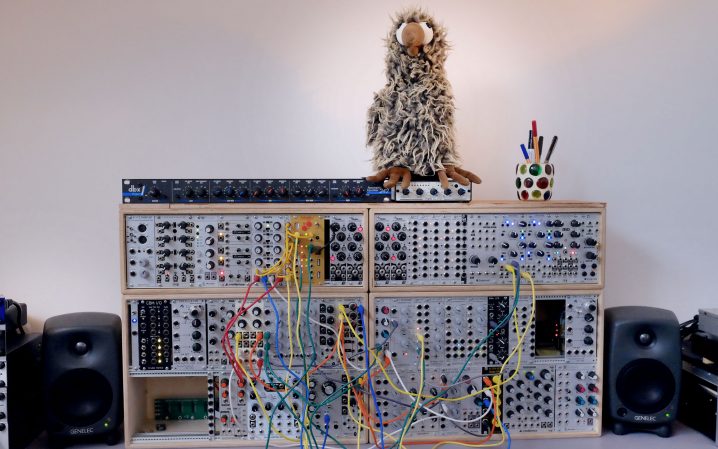

I don’t want to become too much of a collector. I love technology and I admire machines that have a history or are important milestones of technical invention. But it makes no sense to own them all, it would not change the music I make. I have some Yamaha FM synthesizers, a few early digital keyboards including a Synclavier system, a medium sized modular rack, and a lot of hardware reverbs. The hub of it all is my desk with a large screen and computer. There is no mixing console, just a small mixer for processing and routing of outboard gear and a big patch bay. I have eight speakers in my studio, which allow me to either route the stereo sound to a specific place or working in surround.

The studio is only a part of my work, I spend a lot of time coding and I am doing this deliberately not in the studio, but on my office desk. I learned that separating the process of instrument creation, and of using them is very important to me. When I am in the studio I like to work on sound, not on coding. And then there is my work on installations or audiovisual performance pieces which often requires me to rent a bigger rehearsal space.

For a long time, I was hesitant to dive into modular synthesis, I was not convinced I would benefit from it, but I got into it via a detour. I bought a Linn Drum and wanted to filter the sounds and apply envelopes. I built a small modular rack exclusively dedicated to that. And then one thing lead to another. It took me quite some time to find the right modules but now I am very happy with what I have there and it adds new colors to my palette.

Tell us about your favorite piece of hardware.

Nearly impossible to answer, I love them all. The ones I did not fall in love with are all gone. Probably my PPG Wave 2.3 is the winner, followed by the Synclavier. The thing with the PPG is that it sounds like nothing else, it looks like nothing else, and it has knobs to play with. It is complex with a lot of interesting detail, but simple enough to be intuitive. And I cannot get tired of its sound. It is the perfect mix of digital grittiness and analogue filtering. It is also connected to a few records, including ‘Exit’ and ‘White Eagle’ by Tangerine Dream, which were very influential for me, and sometimes I wonder if I like these records because of the sound, or if I acquired a taste for the timbres because of the records. The PPG to me embodies some sort of futuristic nostalgia.

And what about the software that you use for production?

For obvious reasons that is Ableton Live and Max. I write a lot of Max patches and Max4Live devices, it is part of my artistic practice, out of necessity in some cases, and for the fun of it in others. My laser works completely rely on my own tools, and for music production, I sometimes come up with small ideas which I then turn into a ‘special interest’ sound processing / generating device. The most prominent example would be my Granulator synthesizer which became part of the standard Max4Live distribution, and which I still use extensively. I almost never use plug-ins apart from what I create by myself or what comes with Live, which to a varying degree are also things I created. Operator is very much my child and I use it quite often, which is actually a surprise. It was created with the intention to provide a ’nice little FM synth’, and that was it. The reason why I am not diving into plugins that much in general is, that I enjoy the haptic side of hardware too much, and the combination of my hardware plus Max plus Live offers me far more than I ever can explore.

Is there a particular piece of gear that you’re just dying to get your hands on and do you think one day you’ll have it?

Not anymore. There are a lot of lovely historic instruments which I enjoy, but they are all on the same level of excitement for me: A Jupiter 8 is nice, so is an Emulator II, so is an Arp 2600, or a Prophet 5, and so on. Not a single one is totally above all the others, and having all of them, in my opinion, is the death of creativity. From a musical perspective, if I am looking for a specific metallic sound and I have a DX-7 and nothing else, I will find it quite soon. If I have 10 different synths with a similar concept, I might spend way too much time figuring out which machine to use, before even getting started being creative. The collector in me says I want it all. The artist strongly disagrees. Having a physically small studio helps.

However, I’d like to have a cathedral in my backyard, with a huge pipe organ. That would be nice.

Can you please share some aspects of sound design in your work?

I like inharmonic sounds and more dusty textures, I like the grittiness of early digital stuff. I don’t like resonating filters, especially when they sweep in a very obvious way. I like chorusing wide reverbs, and I don’t mind if they are grainy with a lot of audible reflections. Based on those preferences, there are numerous ways to achieve results I enjoy. I am a huge fan of FM synthesis, thus my collection of Yamaha FM Synthesizers, the development of Operator, and my love for the Synclavier, which offers a very different flavor of FM. The other big thing is granular synthesis for me, mainly for creating lush complex textures.

Some projects require a different approach, for my Lumière concerts, I developed a synthesizer which allows me to switch presets at audio rate, 44.100 times per second if I would push it that far. That created its very own constraints, which are reflected back in the results.

Perhaps worth noting is that I don’t find compressors useful at all. I really tried, and I end up each time bypassing them. Whatever compressors can do, I can do better with envelopes and volume automation. To my great surprise, I recently learned that Mark Ernestus of Basic Channel fame shares that notion with me.

Any particular new techniques that you tried out for your last album?

For the VLSI album, I made quite excessive use of my modified Linn Drum, which allows to dramatically pitch its samples. That in combination with filtering and envelopes from my modular rig contributed a lot. And I designed a specific synthesizer for the creation of dense layers of slightly detuned samples. That’s did contribute a lot to backgrounds on the track ‘Geometry Engine’. But the most important change was the fact that I mixed the album with a big console in a fantastic sounding studio together with Mark Ernestus, and that provided me with a lot of unexpected insights. I tend to do too many things alone, and collaborating with a person whose work I admire and who has in parts a very different perspective was an eye opener. It helped me to re-adjust my focus, and that already paid of for a remix I recently did.

What does your live setup look like, and what do you bring with you when you travel for an extensive tour?

The Monolake Live Surround setup is very straight forward: A laptop with Live, a multichannel sound card, a bunch of MIDI controllers. I wanted a system that I can setup and remove quickly, and that uses parts I can get pretty much all over the world, in case things break. It all fits in hand luggage. Lumière is the other extreme; three people traveling, lots of big heavy cases for lasers, computers, etc.

I always spend a lot of time thinking about what to control in a performance situation and how exactly. My favorite MIDI controller is an old Doepfer fader box. I learned to really articulate these faders, and if I assign the right parameters with the correct curves, I can turn that simple piece of gear into a very expressive instrument.

What is the most important environmental aspect of your current workspace and what would be a particular element that you would improve on?

I need daylight. Working in a basement kills me. I also need a space that is clean and organized. That can be a cozy and personal space, but it cannot be cluttered. Every single item in my studio is there for making music. I’d rather compromise other rooms than turning my small studio into a storage space. I also spend a lot of time on work ergonomics, it took me a while to find an arrangement of instruments, speakers etc. which makes working fun and easy. I’d like to dive deep into my machines, and that’s impossible if e.g. a reverb is located in a rack 10cm above the floor. An example: I have an EQ which is routed per default to the output of my noisy Yamaha DX-27. That’s a killer combination, but I would not do it if I had to re-patch it all the time. The EQ is located near the DX-27 and that turns it into an integral part of the setup. Such things are important to me. By placing objects in physical proximity, I create a suggested workflow. It is like synthesizer design: if there is a nice know for filter cutoff, people will play it. Imagine a Roland TR-808 with a tiny display and +/- buttons for parameter adjustment…

What I miss is having more space and lots of plants. My bedroom studio scenario back in the days had that. In my dreams I have a very large good sounding room that works as a music studio, but also as a production space for my installations.

What can you tell us about your overall process of composition? How are the ideas born, where do they mature, and when do they finally see the light?

I have no single strategy here. Some works start from a conceptual framework, others emerge from toying around with the things in my studio. Often I have an idea, I try it out, and it does not do what I want, but on the way I find a detail that catches my attention. Then I try to move on from there. My work is full of detours. Finalizing music is, of course, the biggest challenge. I could change my pieces forever, I find it hard to make a definite statement. That’s were deadlines help a lot. Or a clear conceptual focus.

After the piece is complete, how do you audition the results? What are your reactions to hearing your music in a different context, setting, or a sound system?

It is a painful experience very often. Hearing the work in a different context makes judging an already fragile construction even more difficult. But it is never the less quite important. I learn a lot from listening to my own music together with selected friends. Their presence alone changes my perception of what I am doing. My partner, Susanne aka Electric Indigo is a very helpful reference here. She is always spot on with here evaluations of my work. Playing my music to the wrong people before things are finished can kill it all. One wrong word and I discard everything. But getting feedback from people I trust, and who understand how to approach me in that fragile state is very helpful and appreciated.

I find it actually hard to prepare material for a live show after finishing a track or an album, I just want to move on and not being forced to reflect on what I just did. When I have to listen to my own music I am most of the time just super critical and tend to only hear the flaws.

Do you ever procrastinate? If so, what do you usually find yourself doing during those times?

I read too many newspapers, and I plan to stop that because it does not make me any happier these days. I’d like to improve my procrastination skills, though. Not less of it, but with higher quality. Like spending time with a cup of tea and a good book, or taking care of my plants and then go back to coding or working on music.

What gets you inspired?

Other music, mainly from a non-electronic context, concerts of friends of mine, going to museums, traveling, reading books, and still and forever my occupation with technology. My lasers are very limited machines of expression, they force me to think about what I want to achieve in a very specific way. That is difficult but also inspiring. I am also working on a project that involves learning a very limited and old programming language ( 6502 assembler ), which requires a totally different mindset than coding in high-level languages. Learning that involves reading computer books from the 1980s, and the funny part is, that there is a cultural subtext even in those technical descriptions. That provides inspiration on a very different level.

And finally, what are your thoughts on the state of “electronic music” today?

For a long time, electronic music was strongly connected to technological advances. New synthesis techniques became accessible to a broader group of artists, new interface concepts made it possible to create music in a different, faster, more intuitive way and that naturally shaped the result. We reached a point of saturation here, and technology as a motor for artistic innovation in the domain of sound lost its momentum. Envisioning a new genre emerging mainly from a tool perspective seems unlikely. The area where technology still provides limits is the visual side, and I guess the growing number of artists combining sound and vision reflects that.

Ironically the fact that selling music became much harder these days, could also mean one can stop thinking about it too much. I see a big chance in that evolution, and that’s a more introverted perspective. If I don’t need to worry about new technologies anymore, I can start mastering what I have. If I don’t need to think about sales, because they are so low that it is not big business anyway, I can focus on music which is very personal, instead of trying to copy what already exists and I can try becoming as good in it as possible.

And, times of apparent stagnation in history often turned out to be the moments before something new emerges out of known elements.