Hey Richard, where are you these days, and what have you done this past weekend?

I’m in Cumbria, UK – land of rain and mist, even in summer. Despite the heady 14 degrees C outside, I’ve been indoors for most of the past week, completing music for the soundtrack to a film that I’m about to release.

I wanted to ask you about The Inward Circles – how did this project come about and what is the source of its name?

The name is from ‘Garden of Cyrus’ by the 17th century polymath Thomas Browne, referencing the growth and arrangement of leaves on a tree. It’s the first name I’ve used which is consciously drawn from an external reference. I find his work poignant because it seems to represent that flawed and failed Enlightenment ideal of understanding nature through the application of universal laws. Appropriating his words for my own equally flawed enterprise – understanding nature through music – seemed fitting, and all of the titles for my previous album, ‘Nimrod is Lost in Orion and Osyris in the Doggestarre’, were also adapted from Browne’s various treatises.

When you compose music, do you have an immediate sense of whether a particular work will fall under any of your specific monikers, like A Broken Consort, Clouwbeck, or your real name?

It depends on the context. Often the music is part of a larger concept involving texts, art, photography and – more recently – film. In these situations I know in advance what name the work will be released under. With regard to the other ‘pseudonyms’ – it is really a form of dowsing. The music moves along its own dark channels, and the act of naming is like trying to delimit flow or current patterns. It is also a way of bringing it to the surface. ‘*AR’, the name of my collaborative partnership with Autumn Richardson, is an old Brittonic word meaning ‘springing forth’, and this is an apt metaphor for how the music, through the giving of a name, enters the public domain. It comes from the dark into the light.

And what about your process on selecting the different imprints, like Sustain-Release versus Corbel Stone Press?

There was a small crossover period, but I retired Sustain-Release in 2011, along with those six names, retaining only ‘Richard Skelton’. They belong to a particular period of history. Admittedly, I did begin the Archival Series in 2013, through which I continue to publish previously unreleased or reinterpreted music from the Sustain-Release years. These albums are made available via Aeolian Editions, a digital site which hosts most of the Sustain-Release and Corbel Stone Press catalogue.

Now onto Belated Movements… How did you first come up with the concept for this tribute (if I may call it that?)

I wanted to draw attention to the rather inhumane way in which we treat ‘bog bodies’ by artificially preserving and exhibiting them. Clearly there is much to be learned from their remains, but I’m deeply ambivalent about the whole process of exhumation itself. It interrupts a centuries-old, crushing embrace with the earth – a profound exchange through which the body becomes transformed and ultimately assimilated. Returned from whence it came. Irregardless of the motive or circumstances of their interment – which we may never know – the process, once begun, has a kind of earthly sanctity which needs honouring in some way.

What would you say is our (human) fascination (and fear?) is with the decay, decomposition and disintegration?

It’s a cultural norm to be afraid of death and its signifiers, perhaps stemming from the instinct for self-preservation. But there is also a concomitant fascination with it – a morbid attraction. Ten years ago, when I began visiting the ruined dwellings on the West Pennine Moors of northern England, I felt a similar pull – ruins make us aware of our own mortality, and being reminded of the preciousness of life – perversely – makes us feel more alive. But over the subsequent years I’ve come to appreciate the positive, regenerative aspects of decay. The organisms which facilitate it are part of a natural cycle – focusing on one aspect of this cycle is to miss the bigger picture.

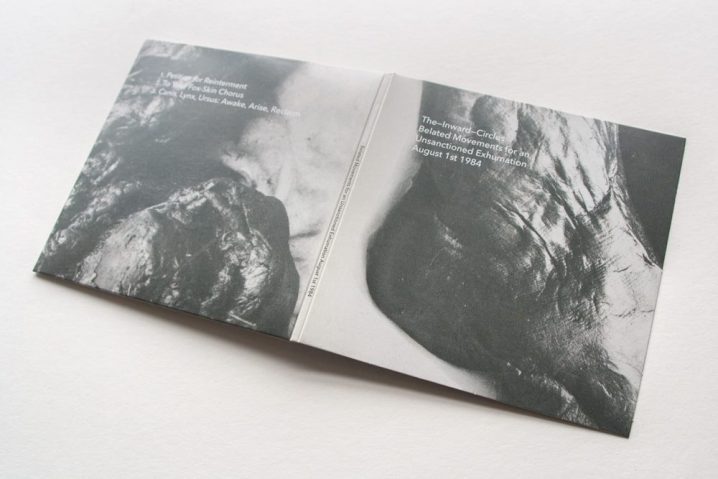

Can you talk about the cover art selected for the album? It definitely strikes an immediate impression. Was that your intent?

I wanted to find quite an ambiguous image, something that could be interpreted as topographical, geological or anatomical. A cliff face, the body of a mountain, the neck of a river. Just as bog bodies slowly become part of the landscape they inhabit, so I wanted to blur the lines between human and non-human. Hopefully something of that sense is communicated.

Did you use any specific new techniques that you have developed for the album?

With ‘Petition for Reinterment’ in particular, I tried to use techniques that imitate the process of decomposition and transformation. In bog bodies the skin is usually perfectly preserved (if stained a deep peat-brown), but the bones often decalcify and ooze. In much of my previous work, I’ve tried to preserve the character of the original acoustic recordings, but with ‘Belated Movements’ I wanted to actively transform it. As with the first Inward Circles album, which was concerned with the processes of weathering, this effectively involved recording a ‘complete’ album and then re-recording the sound of it resonating through various wooden or metal objects and surfaces. I then subjected these recordings to further transformations – various kinds of distortions and modulations that evoked the sensation of centuries-old interment in earth.

When working on long pieces, how do you bracket the amount of time dedicated to each track? Is it a conscious effort?

I don’t think about duration at all. Certainly it’s true that I’ve become more drawn to long-form compositions. As most of my work engages with landscapes in some way, perhaps it’s a way of trying to come to terms with their enormity. It also feels as if there is less ego involved in ‘slow music’ – it’s less eager to please, to satisfy – it doesn’t clamour for attention – although it does require it, nevertheless. It’s not ‘ambient’ music. I prefer to think of it in similar terms to Pauline Oliveros’ concept of ‘deep listening’ – music that helps precipitate total engagement, awareness, consciousness.

But to answer your question – I don’t necessarily set out to make long compositions. The sounds I end up working with usually suggest their own duration. Some work better if they unfold over a longer period. There was a piece on ‘Landings’ entitled ‘Rapture’ which was only two minutes long – one of my shortest – but I felt it could go on forever, albeit not in the context of that particular album. So I revisited a few years later and made ‘Rapture (Reprise)’ – a 36-minute, single-track album, which now bookends ‘The Complete Landings’.

richardskelton.wordpress.com | corbelstonepress.com

Questions by HC