It’s easy to see why Brian Eno is still a relevant name in electronic music. After all, the father of ambiance continues to redefine the genre. Where others have taken a mimicking approach, Eno advanced on exploring the boundaries of sound, often gravitating towards generative music, as can be first hand witnessed in his iOS software, Bloom and Scape, developed together with Peter Chilvers. There have been many releases to date in Eno’s 30-year career – too many to attempt to mention in this write-up. Let it suffice to say that my favourite pieces still remain Ambient 1 – Music For Airports (Polydor, 1978), Thursday Afternoon (EG, 1985), and Neroli (All Saints, 1993). I’ll even admit that his latest collaborative works with David Byrne and Rick Holland were not exactly up my alley. But Lux is a whole other story…

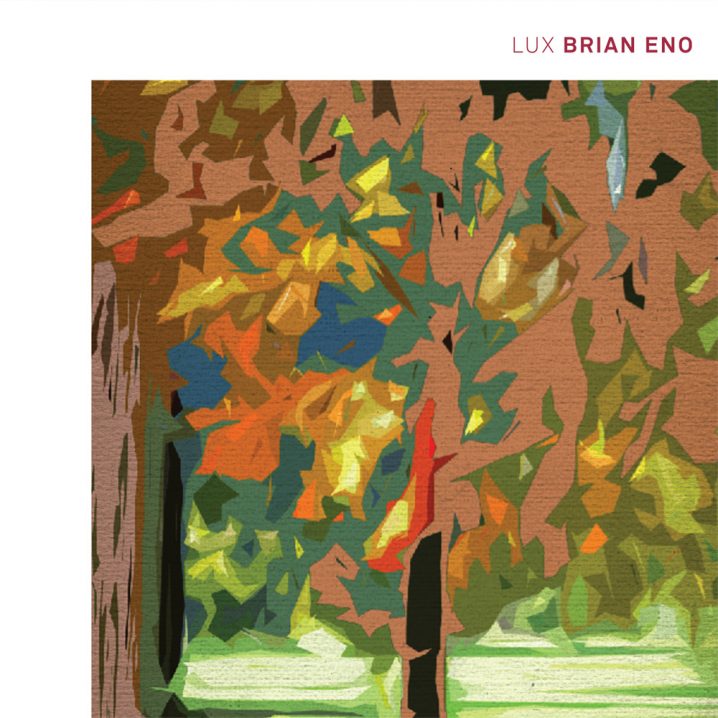

Single notes slash tones slash vibrations slowly fall on the scale like droplets of rain. Individual sounds of various volumes, weight and velocity make up the harmony of variable intervals in rhythm and time. The undertones resonate together, in that feel-good design, the very same way all casinos tune slot machines to C-major. Something about this architectural synergy takes the edge off my misfiring neurons. Perhaps Lux should be played in airports after all [in fact I later learned that Lux was indeed playing throughout Tokyo’s International Airport, Haneda, for a few days in November]. I try to tune into the music and carefully listen. And then I attempt to forget that it’s there. Something, I’m sure, that Eno would definitely like. Instead, I study the album’s cardboard sleeve, with printed designs resembling symbology of John Cage’s scores.

There are four pieces on Lux, all seamlessly blending into each other [note to self: attempt to play the album on random], but the whole 75-minute composition is made up of twelve sections. Originally conceived from a work housed in the Great Gallery of the Palace of Venaria in Turin, Italy, Lux is the first solo album for Eno since 2005’s Another Day On Earth (Hannibal, 2005). There are also four inserts with images by Eno himself. These I can’t connect to music, although I’m sure the key lies in cryptic titles, consisting of chord like tablature with dots on a grid. I’d love to dig deeper, and perhaps deconstruct, but it feels like I will be peeling back the veil of magic that always surrounded music for me. Rather, I let the music fill up my living room, dissolving in its geometry, weather, and space.